What are the real threats from the combination of “verticalization of power” with religion in the Russian-Serbian doctrine of hybrid warfare?

Author: Dr. Gurakuç Kuçi

Senior Researcher at the Institute for Hybrid Warfare Studies “OCTOPUS”

and professor at UNI College

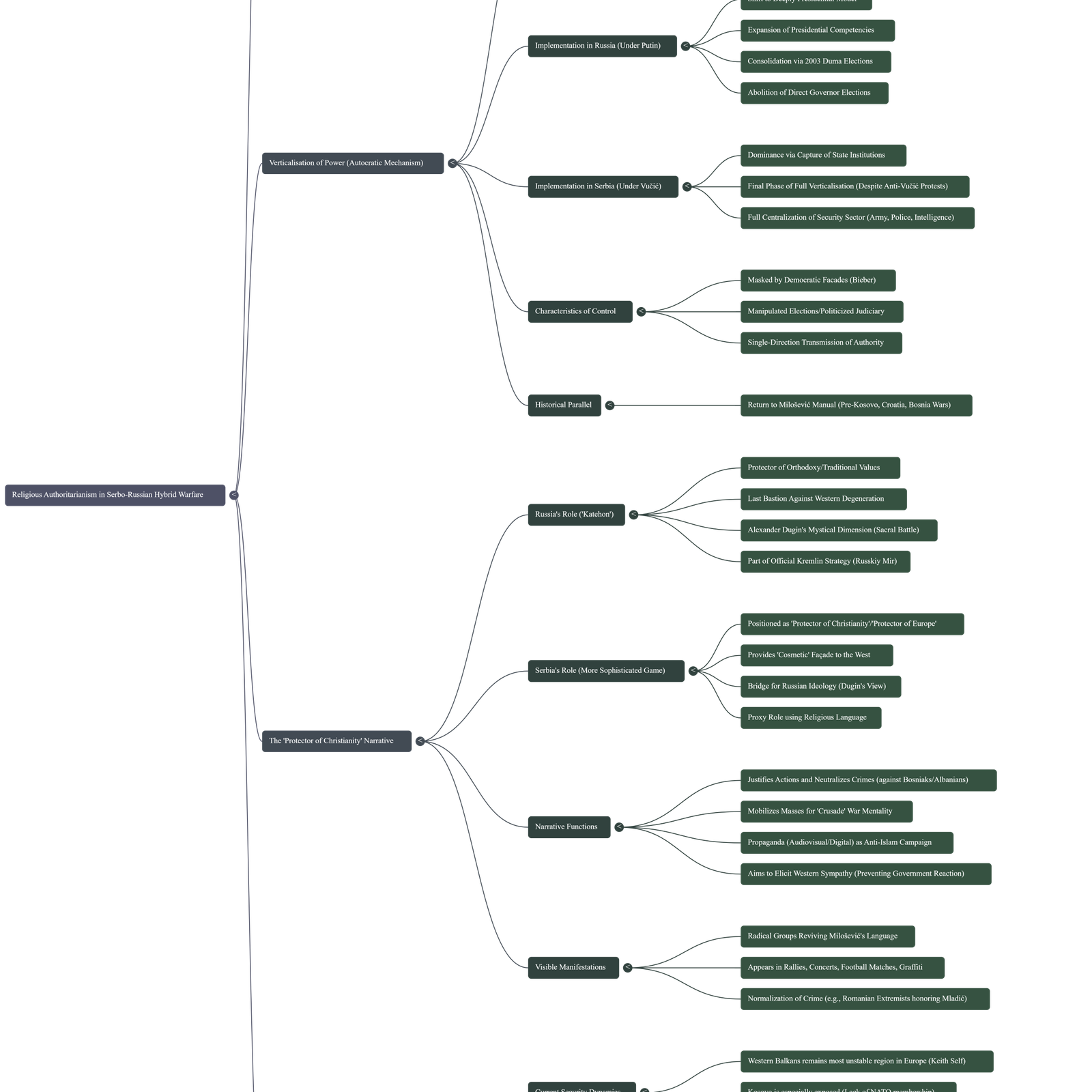

Autocracies rarely invent new methods; they usually recycle those that have worked and adapt them to the circumstances of the moment. Two instruments are activated almost always when an authoritarian regime prepares for external actions: the verticalization of power and the construction of “defender of civilization” type myths. Russia and Serbia are classic examples of this model. Both have built strong top-down control structures, while simultaneously cultivating the narrative that their actions are carried out in the name of “Christianity” or “defense of Europe.” This combination, extreme centralization and political mythology, has served them to mask expansionist ambitions and to create a moral shield that justifies pressure, destabilization, or more sophisticated forms of hybrid warfare.

Vertical power as an autocratic mechanism

In political science, “vertical power” describes the hierarchical concentration of authority from top to bottom, and Serbia, just like Russia, has traditionally demonstrated a full institutional-social synchronisation in its hegemonic policy toward Kosovo. Under Putin, Russia has shifted toward a deeply presidential model: the 2003 Duma elections, the dismissal of the government before the 2004 presidential elections, and the abolition of direct elections for governors consolidated this line. Linz links authoritarianism with limited pluralism and centralized control. According to Levitsky and Way, “vertical power” simply explains the mechanics of this centralization. It dismantles institutional balances and ensures one-directional transmission of authority.

Russia and Serbia apply this model through the extreme concentration of decision making. Putin expands presidential competencies and control over governors, while Vucic builds dominance through the capture of state institutions. According to Bieber, authoritarian regimes mask this control with democratic facades, election manipulation, a politicized judiciary, and submissive legislatures.

Recent developments in Serbia have shown that the country is already in the final stage of full verticalization of power and consolidation of autocracy, despite strong anti-Vucic protests.

For consolidating the verticalization of power, Serbia is implementing full centralization of the security sector. The army, police, and intelligence are being concentrated under the President, including legal reforms, while for BIA alone 89 million euros are planned for 2026, an unusual increase and partially hidden under “confidential programs”. This comes at a time when the United States and its allies are seeking global de-escalation, while Serbia is moving in the opposite direction. Likewise, the new amendments to the Law on the Armed Forces aim to place the Chief of Staff and officers under the direct command of the President, something that does not exist today. And the model is familiar. It is the return of Milosevic’s manual before the wars in Kosovo, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Slovenia. The verticalization of power never moves alone. It is accompanied by the narrative that justifies it.

The “defender” of Christianity and the neutralisation of crimes

Russia, after centralising every link of political power, extended the same verticalisation over the sacred sphere. In the official Russian discourse, Moscow presents itself as “the protector of Orthodoxy and traditional values”, as the last bastion against “Western degeneration”. Aleksandr Dugin has placed this narrative in an almost mystical dimension: Russia as “the katehon”, the force that restrains evil and preserves “true Christianity”. For him, the war in Ukraine is not merely a geopolitical conflict, but a sacred battle against the liberal world. This language has now become part of the Kremlin’s official line, and part of the strategy of the Russian World.

But in the Balkans, the game is more sophisticated. Russia and Serbia share roles but not purpose. Russia is “the protector of Orthodoxy”, something tied to its historical and national identity. Serbia, meanwhile, takes on a broader role. It positions itself as “the defender of Christianity” and “the defender of Europe” from the Balkans. This gives Serbia a cosmetic layer that functions better in the West, and at the same time opens a clean door for Russia to exert hybrid influence. If Russia cannot present itself as a defender of Western Christianity, Serbia can. It has sold itself as such for centuries.

Exactly for this reason Dugin treats Serbia with an almost mythical weight. He sees it as the bridge that makes Russian ideology acceptable in Europe. Serbia creates the facade, Russia supplies all the ideological brain and the strategic core. This is the symbiosis: one has the symbolism, the other has the doctrine.

The Serbian myth of “neutrality” and the small staged frictions with Moscow serve only to create the appearance of an independent actor. In practice, Serbia plays the role of a proxy that uses religious language to justify policies that are in line with Russia.

The return of the sacred element is evident. In Serbia and beyond, radical groups are reviving the same language that Milosevic used before the wars: Serbia as the shield of Europe and Christianity. Today, this is openly displayed in gatherings, concerts, football matches, graffiti, and activities of extremist groups from Serbia, Romania, and other countries.

A clear example: Romanian extremists in Belgrade with a banner calling Ratko Mladic “the European hero who brought Muslims down to zero”. This is not merely provocation. It is the normalisation of crime under the guise of civilizational justification.

The same narrative appeared among Romanian fans in the football match with Bosnia, where Serbia is portrayed as “the defender of Europe”. Inside Serbia, in pro-Vučić protests, radical groups praise war criminals, chant against Muslims, and sell Serbia as a fortress of Christianity. In parallel, Belgrade has become a regular supplier of propaganda campaigns in the region, especially against Kosovo and Albanians, encouraging Kosovo’s neighbouring populations against Albanians and the state of Kosovo.

In this climate, the effects extend even inside Kosovo. Here too, voices are emerging that recycle Islamophobia, penetrating unnaturally into certain groups and media.

Serbia, through the issue of promoting propaganda as “the defender of Christianity”, is dominating the narrative of neutralising the crimes committed against Bosniaks and Albanians.

Current security dynamics as a space for Serbia’s advantages

Geopolitical circumstances today seem to shift between two extremes. One moment there is talk of peace and de-escalation, the next moment fear surfaces that tensions may take a completely different direction. A few weeks ago, the European Commissioner for Defence, Andrius Kubilius, said that German intelligence has information on discussions inside the Kremlin about a possible Russian scenario against NATO.

Meanwhile, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte, from a meeting with NATO Foreign Ministers in Brussels, warned that Russia is “working closely” with China, North Korea and Iran “to disrupt our societies and to destroy global rules” and is “preparing for long-term confrontation”.

Likewise, during the special hearing “Flashpoint: A Path Toward Stability in the Western Balkans” in the House Foreign Affairs Committee, the chairman of the Subcommittee on Europe, Keith Self, warned that in addition to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, the Western Balkans remains the most unstable region in Europe. According to him, Albania, Montenegro and Macedonia would be directly in the line of fire in a renewed conflict, and Kosovo remains particularly exposed due to its lack of NATO membership.

Germany, for its part, has centralised military command and prepared the “OPKAN DEU” plan, a voluminous document that foresees rapid mobilisation and the use of civilian networks for military functions in a crisis. Baltic-Nordic reports for 2024–2025 also warn that Russia is restructuring its forces to have the capacity for both conventional conflict and hybrid forms if the global situation deteriorates.

Russia has denied that it is prepared to attack any NATO or European country outside Ukraine. However, if peace plans do not go as intended, this does not guarantee that the situation cannot escalate.

Conclusions and strategic assessments

As long as Serbia’s engagement in verticalisation and propaganda continues to remain at high levels, and the cooperation of Serbian intelligence with that of Russia and likely also China is at an allied level, this gives us indications that Serbia’s plans, based on the knowledge and preparation conducted with allied intelligence services, go beyond the official reality and that scenarios are being prepared which are not openly articulated.

The verticalisation of power by Serbia enables it to have an architecture for rapid action without delay or accountability. Meanwhile, through sacred propaganda it mobilises the masses and keeps public opinion ready to justify every step taken by Serbia, presenting it as a state engaged in a “crusade”.

A second tool of influence on international opinion, especially Western opinion, is provided by the high levels of propaganda through audiovisual and digital media, where propaganda from these mediums is now almost uncontrollable. This second tool allows Serbia, and consequently Russia, to legitimise their actions as an anti-Islam campaign. The aim is to provoke religious sympathy, and this religious sympathy among pro-Western groups becomes pressure on their governments not to react to Russian-Serbian actions.

In principle, we must understand that none of this has anything to do with genuine religious issues; it is exploitation for division and dominance.

Now, the current phase is one of crisis normalisation, the creation of a condition in which tension is treated as the standard and not as a deviation, while the future remains uncertain precisely because of these models designed to be unpredictable and usable at any moment of opportunism.