Taulant Elshani

senior researcher at the Institute for the Study of Hybrid Warfare

OCTOPUS

Abstract

This study investigates the methods used by Serbia to maintain influence over the Serbian minority in Kosovo, exploring the potential use of these strategies to further Serbia’s regional ambitions in the Western Balkans. The research focuses on various tactics such as media narratives and political maneuvers, aiming to understand their role in Serbia’s strategic goals. By analyzing contemporary practices alongside historical cases, such as Serbia’s narratives during the early 1990s conflicts in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia, this study draws parallels to discern behavioral patterns. Additionally, comparative case studies of Nazi Germany’s use of propaganda about the Sudeten Germans and Russia in the Crimea provide a broader context of state-led ethnic manipulation. This research contributes to understanding how ethnic dynamics are used for political gain in volatile regions.

Introduction

In the complex and volatile landscape of Balkan geopolitics, the discourse surrounding national identity, minority rights and territorial sovereignty often becomes fertile ground for the proliferation of nationalist narratives. This paper delves into the process through which Serbia, using historical grievances and ethnic “solidarity”, is systematically building and distributing a narrative focused on the alleged endangerment of the Serbian minority in Kosovo. Through a focused examination of Serbian state-sponsored rhetoric, media manipulation, and strategic political maneuvering, this study aims to examine the underlying motives and methodologies used by the Serbian authorities in their attempt to create a cohesive national narrative that potentially supports and justifies aggressive territorial ambitions under the guise of protecting ethnic Serbs living outside the borders of the Serbian state.

Drawing parallels with the resurgence of Serbian nationalism in the 1990s, this research traces the historical roots and contemporary manifestations of a hegemonic project aimed at creating a “Greater Serbia”. This effort, characterized by the humiliation of other ethnic groups and the glorification of Serbian victimhood, aims not only to rewrite geographical borders but also to redefine the ethnic and cultural landscape of the Western Balkans. By critically analyzing the rhetoric used during the conflicts in Croatia and Bosnia, this paper elucidates the strategic use of victimization narratives as a precursor to and justification for acts of aggression and territorial expansion.

Additionally, the concept of border relativization, a tactic not exclusive to the Serbian context but applicable to other geopolitical crises, such as Russia’s actions in Ukraine, is also explored herein. This strategy, which challenges the legitimacy of internationally recognized borders based on ethnic composition, is examined through the lenses of historical revisionism and political opportunism. The paper also critically analyzes the role of religious institutions, especially the Serbian Orthodox Church, in advocating a narrative that transcends national borders and invokes a pan-Serbian identity.

Upon placing the contemporary discourse on Kosovo within a broader historical and regional context, this paper aims to contribute to the understanding of how nationalist narratives are constructed, propagated, and used in the pursuit and achievement of political objectives. The research attempts to provide a nuanced analysis of the interplay between ethnicity, nationalism, and state-building processes in the Balkans, focusing on Serbia’s efforts to mobilize historical grievances and ethnic solidarity in the service of territorial ambitions. Through this examination, the study aims to shed light on the wider implications of such narratives for regional stability, inter-ethnic relations, and the principles of international law and sovereignty.

Research Methodology

This study applies a multi-source research methodology to critically examine Serbia’s instrumentalization of minority groups (Croatia, BiH, Kosovo), as a justification for its expansionist agenda. The core of our research material includes a wide spectrum of sources, including a broad review of literature, historical documents, and narratives. Primary sources consist of newspapers from the 1980s and 1990s within Kosovo and Serbia, providing first-hand knowledge of the sociopolitical climate of the period. The secondary sources derive from a comprehensive analysis of academic works studying Serbian nationalism and its ramifications in the Balkans during the 1990s, providing a theoretical and historical context to our study.

Furthermore, this research includes reports from international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), which provide an unbiased view of the issues researched upon, thus enriching our understanding of the attitudes and reactions of the international community. Interviews and online articles have been carefully selected to include perspectives from a wide range of scholar spectrum, including academics, policy makers and those directly affected by the issues at hand. This methodological approach enables a deep and nuanced understanding of the mechanisms through which Serbia has used Serb minority community in Kosovo and elsewhere to advance its expansionist goals.

Research questions

How does Serbia instrumentalize Serb minority populations in Kosovo and elsewhere as a means of justifying its expansionist agenda, and what parallels can be drawn to historical and modern- day examples of state-directed narrative fabrication to legitimize territorial ambitions?

Hypothesis

Serbia uses a systematic approach to instrumentalize the Serb minority population in Kosovo and other regions by fabricating and disseminating narratives that justify its expansionist agenda. This strategy is part of a pattern observed in the state’s behaviour where historical grievances, ethnic ties, and nationalism are manipulated to legitimize territorial claims.

Fabrication of the narrative

Strategic distribution of information warfare

One of the most useful levers for Serbia to extend its influence and to implement its expansionist plans in the Western Balkans are the Serbian minorities living outside the borders of the Republic of Serbia. It seems that Serbia has intensified the use of strategic fabrication of reality in the Balkans by spreading the idea that Serbs as minorities are in danger, the same as Slobodan Milosevic’s regime did in the early 90s.

Serbia, under the leadership of Aleksandar Vučić, has increasingly used information warfare and the construction of fabricated narratives as a cornerstone of its foreign policy strategy. This approach is aimed at shaping and changing perceptions at the global level, especially against the Republic of Kosovo. The Serbian government’s propaganda efforts are precisely designed to portray Kosovo as a state engaged in the ethnic cleansing of Serbs, thereby positioning Serbia as a defender of human rights and ethnic minorities. This narrative serves multiple purposes, including justifying Serbia’s geopolitical ambitions and galvanizing international sympathy and support.

At the centre of Serbia’s state propaganda is the portrayal of Serbs as a threatened minority, not only within Kosovo but throughout the Western Balkans as well. This fabricated narrative, systematically promoted by high-ranking Serbian officials – from President Aleksandar Vučić, Prime Minister Ana Brnabić, as well as through the activities of Serb List (Srpska Lista) in Kosovo, various media and Serbian diplomatic channels, including Ambassador Marko Djuric to the United States — serves the agenda and long-term plans of the Serbian state. This rapid spread of a perceived threat to the Serbian minority is used to consolidate domestic and international support, to legitimize Serbia’s political and military positions, and to undermine Kosovo’s sovereignty and image on the global stage.

A notable example of Serbia’s strategy to internationalize the narrative of “threatened Serbs” occurred during a special session of the United Nations Security Council on 8 February 2024. The presentation of a report by President Vučić, which allegedly discussed the restriction on Serbian dinar in Kosovo, in reality, had content without real evidence and his speech reflected what Dobrica Cosic would underline as “lying is a form of Serbian patriotism”, it was universally documented for the content of misleading and false statements. The president of Serbia’s claims, made during this Security Council session, were dismissed as inventions and untruths by the European Stability Initiative’s report (ESI, 2024). The ESI report documented that mass emigration was the main cause of the decrease in the number of Serbs in Serbia and elsewhere. This speech, characterized by its accusing tone and controversial claims, underlined Serbia’s intention to use international platforms and institutions to spread and legitimize its fabricated narrative, thereby trying to influence global politics and perception.

Russian support in information warfare and diplomatic role

The alignment of Russian foreign policy with Serbia’s propaganda campaign further complicates regional geopolitics. The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs has issued statements accusing Kosovo of violence and ethnic cleansing against Serbs, mirroring the rhetoric used by Serbian officials (Zakharova, 2024). This synchronization between Russian and Serbian propaganda efforts is indicative of a broader alliance aimed at destabilizing the Western Balkan region,

undermining the influence of the Euro-Atlantic alliance, and legitimizing their respective political and military objectives under the guise of protecting ethnic minorities (Shedd & Stradner, 2023).

The Serbian Embassy in the United States, led by Ambassador Marko Djuric, has been decisive in promoting the narrative of “threatened Serbs” beyond the Balkan region. Through numerous conferences and events held in major US cities, the Embassy engages by inviting political, cultural, and religious figures to spread its rhetoric and purpose for Kosovo and for the “living conditions of the Serbian minority” (Kosovo Online, 2023). These efforts characterized by the presentation of unverified or distorted information, aim to influence American institutions and society as well as international opinion and gain support for Serbia’s policies.

The effectiveness of political propaganda in shaping public opinion and international politics is well-documented in the political science literature. The use of such tactics by Serbia against Kosovo, and therefore against other neighbouring countries, is a symbol of a sophisticated strategy used by state actors seeking to exert their influence and justify actions on the international stage. Theoretical frameworks dealing with information warfare and narrative fabrication provide a lens through which one can critically analyze the motivations and implications of Serbia’s actions. Ultimately, the purpose of playing lies about alleged violence against minorities is clear: the preparation of the geopolitical ground for intervention, aggression, and other malicious activities under the pretext of protecting ethnic minorities (Zevelev, 2016). This strategy not only represents a direct challenge to the stability and sovereignty of Kosovo but also to regional peace and international norms that somewhat regulate the present-day world order.

Resurgence of Serbian nationalism

In November 1991, Serbian Patriarch Pavle sent a letter to Lord Peter Carrington, Chairman of the Conference on the former Yugoslavia. In this letter, Patriarch Pavle expressed concern about the “difficult” situation, as he put it, faced by the Serbs in Croatia, suggesting that they faced a choice between armed defense and expulsion due to the creation of the independent state of Croatia. The patriarch Pavle was very active in advocating and affirming the idea that Serbs could not live in an independent Croatia but should unite with their home country, i.e., proper Serbia.

In his letter, among other things, Patriarch Pavle wrote: “As a centuries-old guardian of Serbian spirituality and national and cultural-historical identity, the Serbian Orthodox Church is particularly concerned about the fate of the Serbian people at this turning point. For the second time in this century, the Serbian people face genocide and expulsion from the territories where they have lived for centuries” (Tomanić, 2021). This was undoubtedly an ominous warning of the catastrophe that was to follow in the Balkans.

Figure 1 War in Bosnia and Herzegovina April 6, 1992 – Photo https://www.slobodnaevropa.org/a/the-balkan-wars-1991-1995-a- sketch/25407574.html

What does raising the alarm about the alleged “genocide” that awaited the Serbian people tell us? At the beginning of the 90s, right after the collapse of the edifice called Yugoslavia, the Serbian elite was charged with the task of “rediscovering” the Serbian national identity. The Serbian Orthodox Church was centered on the spiritual awakening of the Serbian people; The League of Serbian Writers tried to take care of the literary aspect and the interpretation of medieval myths; The Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts was charged with academic and scientific emancipation (Tomanić, 2021). The ideological basis on which these institutions worked and the cause they served was Serbian nationalism, while the goal was a Greater Serbia that would bring all Serbs under one roof.

Serbian nationalist elites, led by figures such as Slobodan Milosevic, skillfully manipulated ethnic identities and historical narratives to portray Serbs living in Croatia and Bosnia as jeopardized minorities. Through a joint media campaign and political rhetoric, these elites propagated stories of historical injustices and current threats facing Serbs in these regions (Judah, 2008). The presentation of Serbs as victims in need of protection served to legitimize the call for military intervention, which would be only the first act of the Greater Serbia idea. Thus, the propaganda goal of Serbian nationalism was to instill the idea that Serbs faced imminent danger, and in case they did not hurry to join Serbia they risked total extinction (Tomanić, 2021).

The fabricated narrative of “a jeopardized Serbian minority” under siege by nascent sovereign states was the cornerstone of Serbia’s justification for military intervention in Croatia and Bosnia. This intervention was framed as a protective measure, necessary to secure Serbs from the delusion of “genocide and persecution” – a portrayal that sought to echo in the collective memory of Serbia’s past in the Second World War (Cox, 2002). By framing the military campaigns as efforts to defend their nation and people, Serbian leaders sought to galvanize domestic and diaspora support for their cause.

Figure 2 The map of Greater Serbia proposed by the chairman of the Serbian Radical Party Vojslav Sesel – Photo https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q746607#/media/File:Map_of_Greater_Serbia_(in_Yugoslavia).svg

The fabricated narrative about jeopardized Serbs, which was supposed to create the circumstances and conditions for the military interventions in Bosnia and Croatia, has been critically examined and challenged by a wealth of scholarly works and historical data. Contrary to the claims propagated by Serbian nationalist elites, evidence suggests that the portrayal of Serbs as being on the brink of genocide was a strategic fiction designed to mobilize support for the creation of Greater Serbia through military invasions and atrocities. In her analysis of the causes of the crisis

in Yugoslavia, Serbian author Vesna Pesic argues that “Kosovo demonstrated that ethnic conflicts could be invented and exacerbated through media propaganda. This effective tool became the principal mechanism for intensifying ethnic conflicts in Yugoslavia (Pesic, 1996).

First, the idea that Serbs in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina were under threat served primarily as a pretext for advancing nationalist objectives, rather than a response to real threats. Many academic research confirm that, at the beginning of the breakup of Yugoslavia, there was no substantial evidence indicating a systematic effort to persecute or jeopardize the Serbian population in these republics. Instead, Serbian nationalist leaders, using the collective memory of the past, manipulated historical grievances to create a narrative favourable to their political agenda (Pesic, 1996).

The academic criticism of the alleged jeopardized Serbian minority narrative is supported by a considerable body of evidence, including diplomatic communications, reports from international observers, and testimonies of victims of the conflict. These sources collectively dismissed the myth of a threatened Serbian minority, “debunking” a calculated campaign of nationalist propaganda that served as a facade for the violent creation of Greater Serbia. The opposite is true, as confirmed by the official indictment of the Hague Tribunal against Milosevic, that Serbia and its leadership were “responsible for the genocide and violence in the former Yugoslavia” (ICTY, 1999).

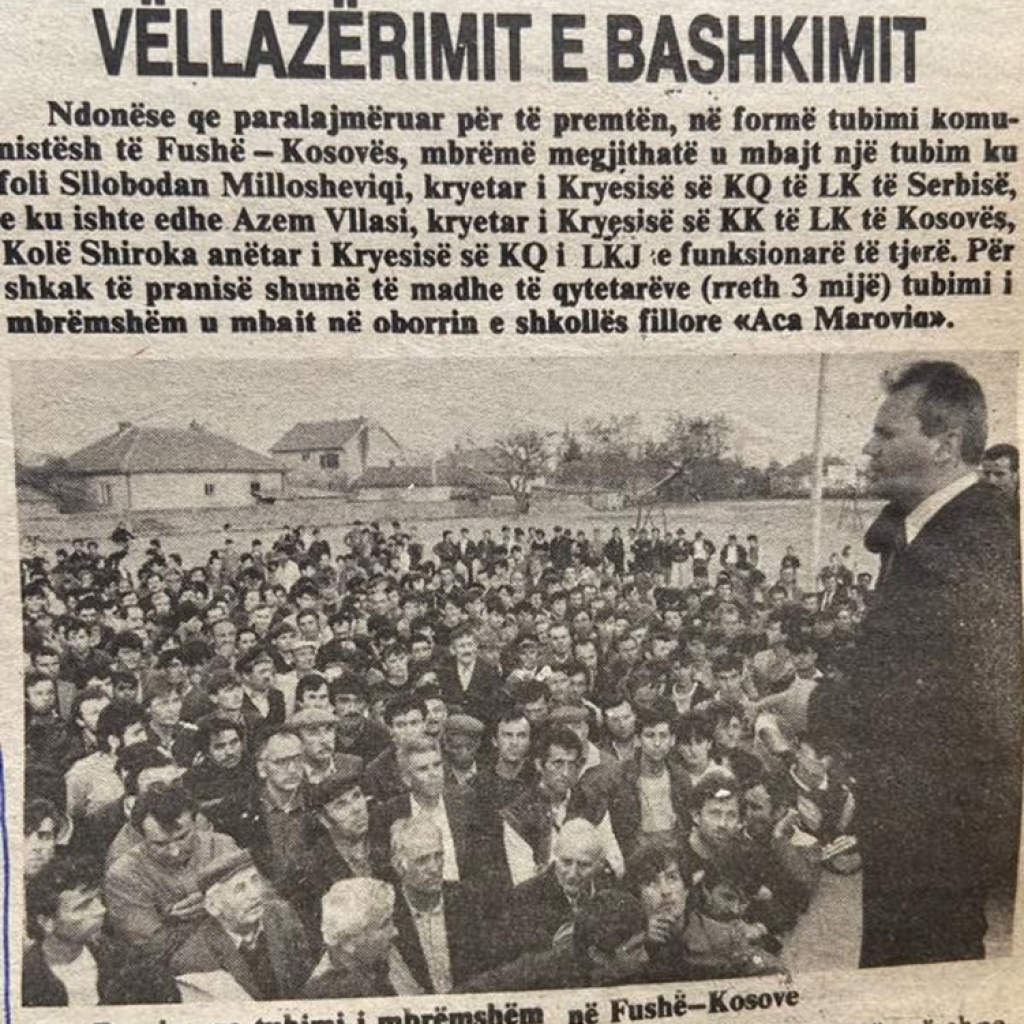

The project for a greater Serbia was “presented” very aggressively and pompously first in Kosovo. To analyze the resurgence of aggressive and primitive Serbian nationalism, it is essential to examine a fundamental moment that has profoundly influenced the political landscape of the region: Slobodan Milosevic’s infamous rally on 20 April 1987, in Kosovo Field (Fushë Kosova). This event marked a critical point in the escalation of nationalist rhetoric, catalyzing the spread of a false Serbian narrative centered on the notion of a constantly threatened Serbian identity (Giffoni, 2020). Such narratives have been instrumental in justifying Serbia’s hegemonic ambitions in the Balkans, under the guise of protecting ethnic Serbs, thus promoting the Greater Serbia ideology.

Figure 3 Milosevic Speech – Fushë Kosova 1987

The Fushë Kosova rally is emblematic in terms of mechanisms through which political leaders exploit historical grievances and manipulate collective memory to foster support for nationalist causes. By proclaiming: “No one should dare to beat you”, Milosevic not only positioned himself as the defender of the Serbian people but also legitimized the use of force in the name of national security. This rhetoric is precisely designed to evoke a siege mentality, portraying Serbs as victims of historical injustices and present-day aggression, despite the lack of evidence to substantiate such claims.

This strategy is not limited to the historical context of the late 80s, but continues as a powerful tool in contemporary Serbian politics. Trumpeting the narrative of threatened Serbs serves multiple functions: it consolidates domestic support by rallying the population around a common cause, diverts attention from domestic issues, and seeks international sympathy by portraying Serbs as perpetual victims (Bechev, 2024). Such tactics are not simply historical reflections but are actively used in current political discourse, indicating a deliberate pattern of behaviour intended to justify aggressive postures and, potentially, future military interventions under the pretext of pretecting “national interest”.

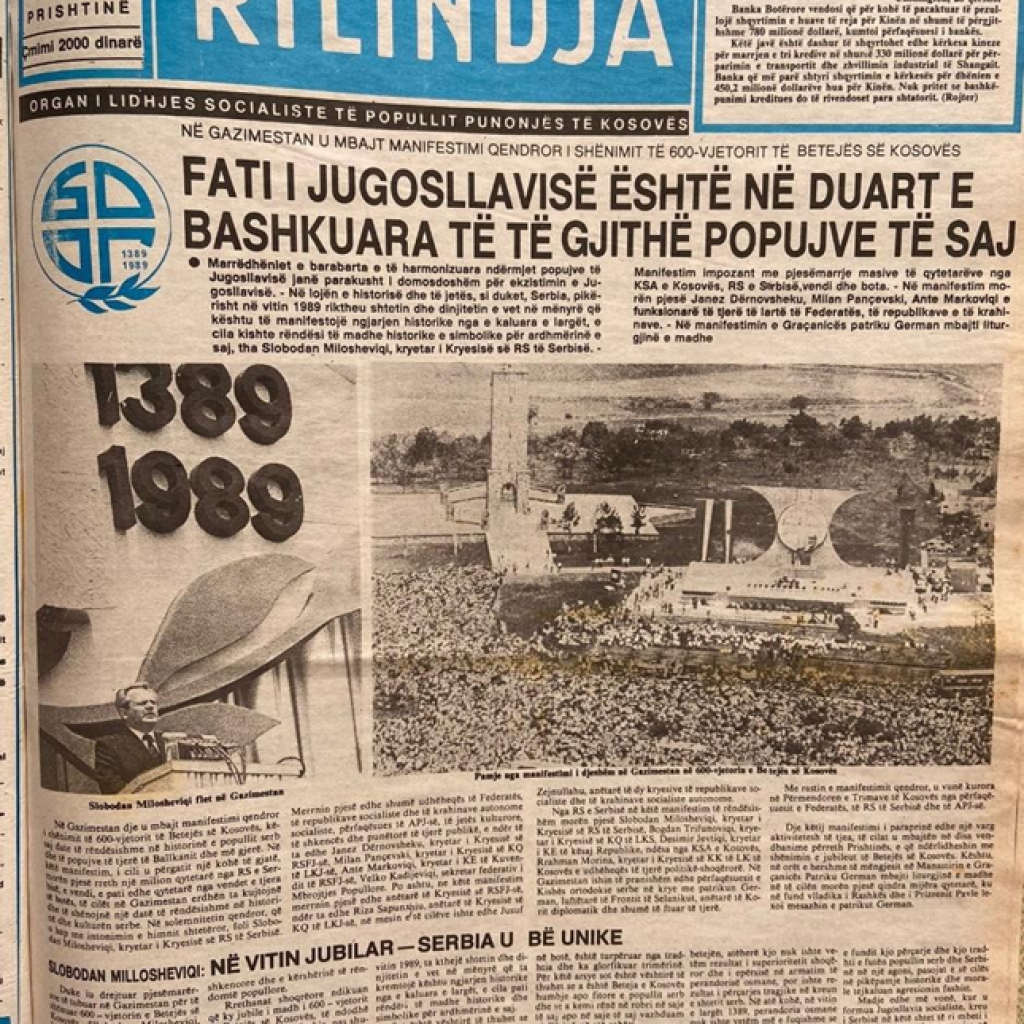

Figure 4 Milosevic Speech – Gazimestan 1989

The strange historical meeting of Tito and Lenin

The latter part of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century have witnessed a resurgence of nationalism as a determining force, capable of reshaping international borders and boosting geopolitical conflicts (Tamil, 2019) . This resurgence is epitomized by the actions and rhetoric of nationalist movements in Serbia during the 1990s and in Putin’s Russia in 2022. A comparative analysis of these periods sheds light on a list of very similar geopolitical games: the instrumentalization of ethnic minority narratives to justify the interventions, hybrid war, and territorial ambitions.

In the ‘90s, the Serbian Orthodox Church, alongside Serbian nationalist elites, propagated a policy that challenged the legitimacy of Croatia’s borders. These borders, they argued, were artificially drawn by Tito and did not reflect the ethnic realities of the region (Tomanić, 2021). By framing these borders as non-historical and therefore malleable, the narrative served to undermine Croatia’s sovereignty and validate Serbian territorial claims, especially in Republic of Serbian Krajina. This rhetoric not only stoked the fires of nationalism within Serbia but also laid the groundwork for a strategy of territorial expansion under the guise of protecting ethnic Serbs.

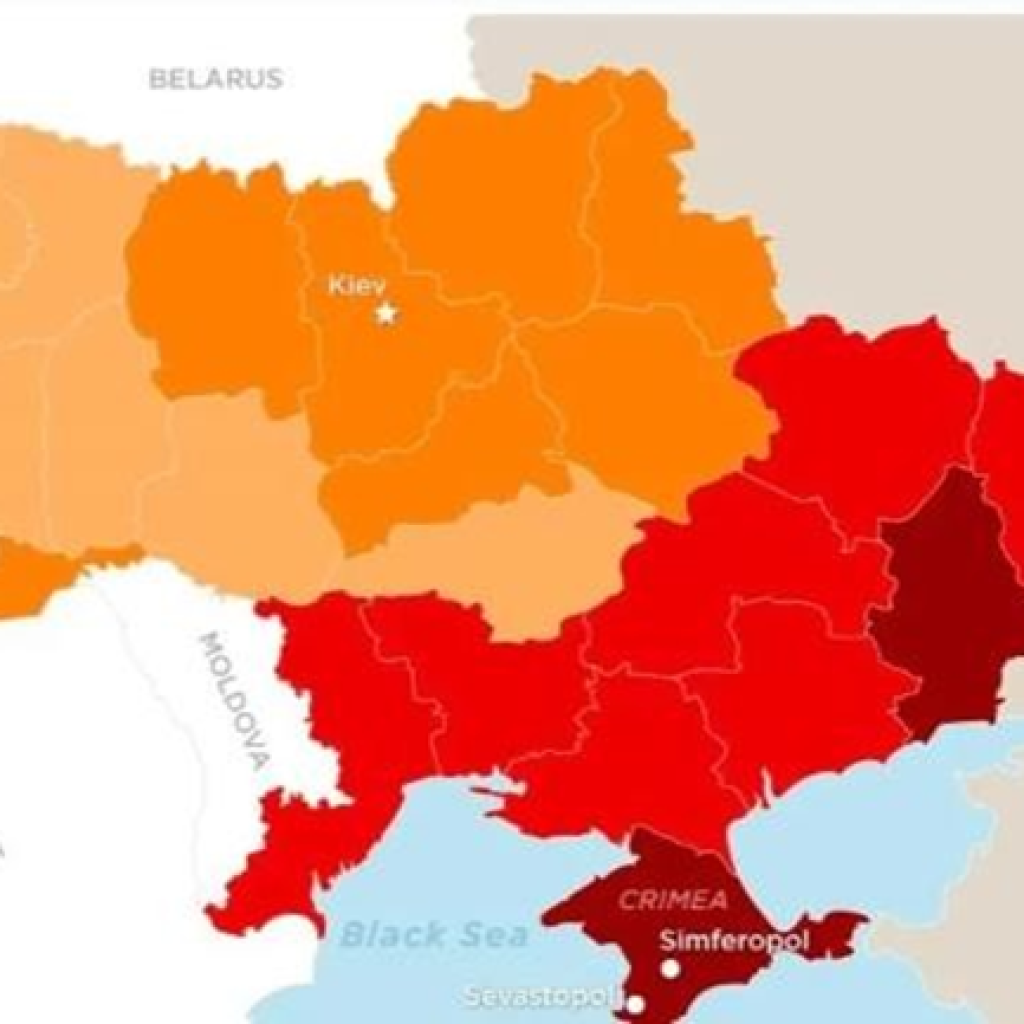

Back in 2022, Vladimir Putin’s Russia used a strikingly similar argumentative framework to justify his aggressive stance toward Ukraine. Putin claimed that Ukraine’s borders were a Soviet-era construct drawn by Lenin that lacked ethnic legitimacy, questioning Ukraine’s sovereignty and rationalizing Russian intervention (Plokhii, 2022). This narrative served a dual purpose: it appealed to Russian nationalism by evoking historical grievances, and it lent a layer of legitimacy to Russia’s annexationist ambitions.

Figure 5 Russian as a native language – Photo https://www.forbes.com/sites/realspin/2014/03/13/the-ethnicities-of-ukraine-are- united/?sh=16e2b70d110e

Both cases show how state actors can use invented historical narratives and ethnic identity politics to advance their geopolitical goals. The Serbian Orthodox Church’s relativization of Croatian borders and Putin’s denial of Ukraine’s sovereignty are not mere rhetorical devices; they are indicative of a deeper strategy of exploiting ethnic minority issues to justify expansionist policies. In doing so, these actors engage in a form of hybrid warfare that blurs the lines between

conventional military aggression and cultural-ideological conflict, aiming to destabilize and delegitimize target states from within.

Moreover, Russia’s instrumentalization of Russian minorities in “Near Abroad” echoes Serbia’s strategy in the Western Balkans, revealing a consistent pattern of using ethnic compatriots as a geopolitical tool. This strategy is not limited to military or political intervention but extends to fostering cultural ties, supporting pro-Russian sentiment and even granting Russian citizenship to Russian minorities in neighbouring countries and beyond. Such tactics aim to create spheres of influence that extend far beyond traditional state borders, challenging the post-World War II international order and the principle of the inviolability of national borders.

The parallels between nationalist movements in Serbia and Putin’s Russia underline a more complex trend in international relations: the resurgence of ethnic nationalism as a force capable of challenging the global order (Huntington, 2011). These situational analysis serve as a strong reminder of the power of nationalist narratives and the ease with whereby they can be instrumentalized by state actors seeking to expand their influence and territory. As the international community confronts these challenges, understanding the historical and ideological underpinnings of such movements becomes essential in formulating effective responses to the complex interplay of nationalism, sovereignty, and territorial integrity.

Between Dreams and Realities: Serbia’s Path to Hegemony in the Western Balkans

Nationalism, Aleksandar Vučić, and Russian support

Serbian nationalism, deeply rooted in medieval narratives, mythologized history, and ideological constructs, plays a decisive role in the political processes of the modern Serbian state (Cox, 2002). The revival of this expansionist nationalism can be traced to the formulation of “Nacertanije” by Ilija Garašanin in the 19th century. This document laid the foundations for a Greater Serbia ideology, emphasizing the unification of all Serbian territories, a subject that has repeatedly resurfaced in Serbian political action. Similarly, the “homogeneous Serbia” manifesto drafted by Stevan Moljević on 30 June 1941, and the Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU) of 1986 have played a critical role in reviving and sustaining nationalist sentiments. These documents collectively advocate for the consolidation of Serbian territories and the protection of the Serbian population outside Serbia’s official borders, underlining an ongoing vision of national homogeneity and expansionism (Beljo, 1999). This nationalist hidden stream is not a relic of the past, but a living ideology that significantly influences present-day Serbian politics, shaping its interactions with neighbouring countries and its treatment towards the minority populations.

The autocratic leadership of Aleksandar Vučić has further strengthened Serbia’s nationalist ambitions. Vučić, using his authoritarian model of governance, has positioned himself as a key figure in pursuing the dream of a “Serbian World”. His leadership style, characterized by tight control over the media and political divisiveness, reflects his ambition to achieve the political goals stemming from the aforementioned documents for Serbian hegemony (Meadow, 2022). This ambition is consistent with historical Serbian hegemonic aspirations but is pursued with modern political strategies and tactics. Vučić’s approach is typical of an established trend in Serbian politics; where historical goals are intertwined with personal ambitions, shaping the country’s domestic and foreign policies. His vision for Serbia extends beyond mere territorial claims, aspiring to a cultural and political hegemony in the Western Balkans that resonates with nationalist narratives of the past.

The role of international power dynamics, particularly Russian support, is essential in Serbia’s pursuit of nationalist ambitions. Russia, which shares an Orthodox Christian heritage and Slavic brotherhood with Serbia, has been a staunch ally, providing diplomatic, economic, and military support historically. This alliance is strategically beneficial for Russia, providing a foothold, a field to growing its influence in the Western Balkans, and a means of exerting impact in Europe. For Serbia, Russian support strengthens its position against Western pressure and sanctions, enabling it to pursue its objectives more aggressively. This symbiotic relationship underscores the geopolitical chess game in the region, where Serbia’s aspirations are intertwined with Russia’s global ambitions to challenge Western hegemony and expand its influence.

Figure 6 Vučić meets Putin at the Kremlin, Moscow – Photo https://www.rferl.org/a/vucic-expresses-deep-gratitude-to-putin-as- serbian-russian-leaders-meet-at-kremlin/29521732.html

Serbia’s hegemonic aspirations in the Balkans, fueled by a combination of historical narratives, nationalist ideology, and leadership ambitions, pose significant risks. The quest for dominance, reminiscent of past conflicts, threatens to destabilize the region, provoking tensions and potentially catastrophic conflicts. Serbia’s actions, driven by the aim for territorial and political hegemony, challenge the principles of sovereignty and territorial integrity, echoing the dangerous precedents created in the 90s. The potential for unprecedented violence and destabilization is a strong reminder of the destructive power of uncontrolled nationalism and hegemonic ambitions.

Western reaction and peace politics

The Western response to Serbia’s actions, characterized by a strange reluctance to impose punitive measures against the Vučić regime, reflects a major dilemma in international politics. The policy of appeasement, aimed at maintaining stability and avoiding confrontations, has proven to be counterproductive. This approach encourages Serbian nationalism and its territorial ambitions, undermining efforts to promote peace and stability in the region. The lack of decisive action against Serbia not only facilitates the continuation of its aggressive policies but also signals a dangerous precedent for international relations, where aggressive positions and expansionist ambitions face restricted resistance.

Serbia’s current ambitions in the Western Balkans, supported by a complex interaction of nationalism, leadership, and international dynamics, present a significant challenge to regional stability and international norms. Plans for a “Serbian world”, fueled by medieval historical myths and modern political ambitions, are fraught with risks of conflict and instability. The response of the international community, especially that of the West, will be decisive in shaping the future trajectory of the region, emphasizing the need for a more assertive and principled approach to preventing the recurrence of past conflicts.

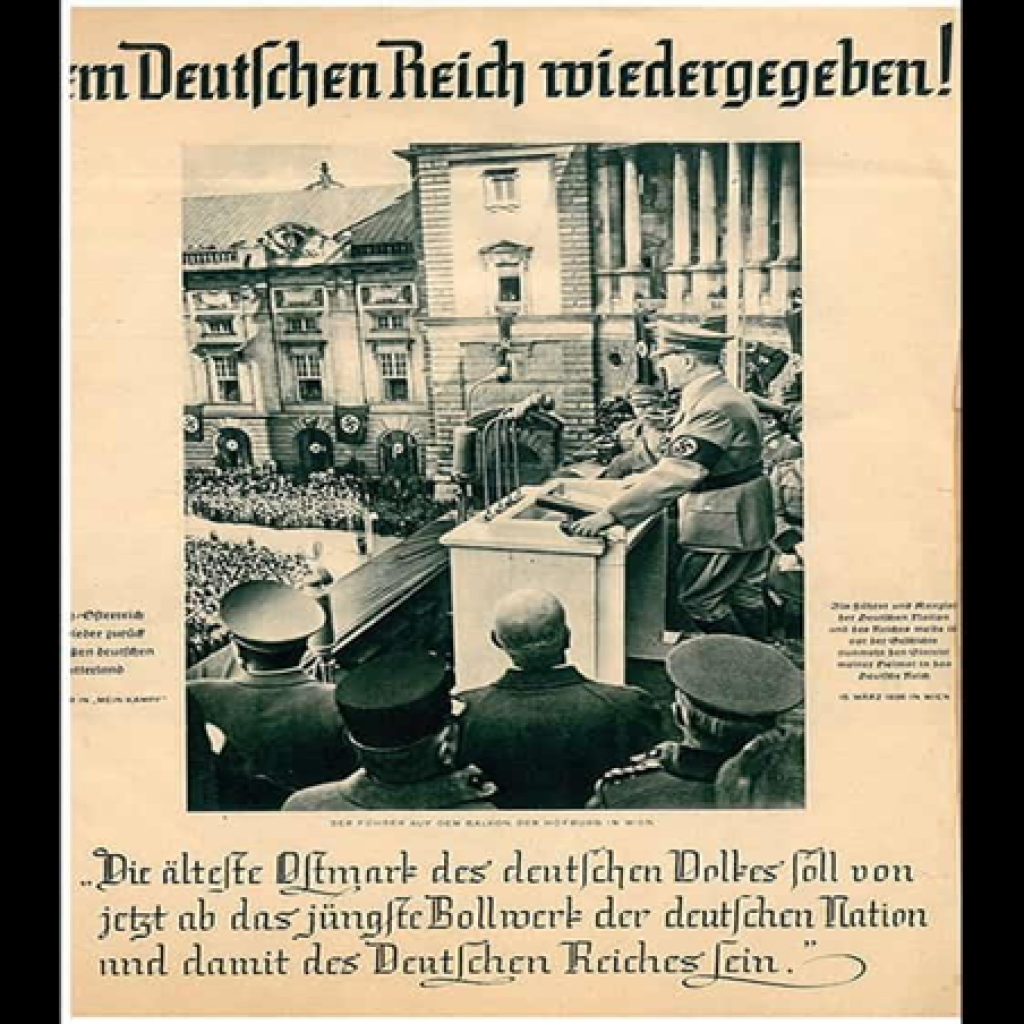

Case Study: The annexation of the Sudetenland – a prelude to expansion

The annexation of the Sudetenland by Nazi Germany in 1938 is a stark historical example of how fabricated narratives about threatened minorities can be strategically used to justify territorial expansion and aggression. This case study delves into the mechanisms used by Adolf Hitler and the Nazi regime to portray the German-speaking minority in the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia as oppressed and jeopardized, establishing a pretext for annexation and warning the larger ambitions of territorial expansion that would characterize Europe in the Second World War.

Fabrication of the narrative

Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Germany was accompanied by a revival of nationalist enthusiasm and the doctrine of Lebensraum (living space), which advocated the expansion of German territories to accommodate the presumed needs of the growing German population. Central to this ideology was the assertion of the unification of all ethnic Germans under one state. The Sudetenland, with its substantial German-speaking population, became a focal point for such ambitions (Nelsson, 2021).

The Nazi propaganda machine began by frequenting and distorting incidents of cultural and linguistic discrimination against the Sudeten Germans. The portrayal of Sudetenland Germans as

Figure 7 Local newspaper reporting the annexation of the Sudetenland – Photo https://www.theholocaustexplained.org/life-in- nazi-occupied-europe/foreign-policy-and-the-road-to-war/occupation-of-the-sudetenland/

victims of Czechoslovak oppression was systematically broadcast through various platforms, including newspapers, radio broadcasts, and public speeches by Nazi officials. This narrative was further supported by staged incidents and fake operations designed to give the impression of large- scale persecution. The film Schicksalswende is the most descriptive case of the Nazi propaganda machine, which prepared the ground for the annexation of the Sudetenland (Haussler & Scheunemann, 1939).

The Munich Agreement of 1938, where Czechoslovakia was forced to cede the Sudetenland to Germany without a direct conflict, was an immediate consequence of the fabricated narrative of oppression. The international community, led by Britain and France, adopted a policy of appeasement, believing that meeting Hitler’s territorial demands would prevent a larger conflict (Nelsson, 2021). This miscalculation underscored the effectiveness of Nazi propaganda and the underestimation of Hitler’s expansionist intentions.

After the annexation, the narrative quickly shifted from the protection of oppressed Germans to the complete annexation of Czechoslovakia and further expansionism to the east. The occupation of the Sudetenland served as a strategic military advantage, leading to the final breakdown of Czechoslovakia and setting the stage for further Nazi aggression in Europe.

This case study provides a valuable perspective when examining similar narratives in contemporary geopolitical conflicts, such as the situation in the Balkans, more specifically Serbia’s strategy of using Serbian minorities in neighboring countries for its regional influence. The tactics of fabricating minority threats, exploiting international responses, and exploiting historical grievances bear striking similarities, underscoring the importance of critically evaluating such narratives and the motives behind them.

Case study II: The annexation of Crimea – the reminiscence of the Sudetenland

Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 provides a more recent example of how narratives of protecting threatened minorities can be used to justify territorial expansion. Here, the Russian government claimed to protect the Russian-speaking population of Crimea from Ukrainian oppression, reflecting the Sudetenland pretext. The international response, characterized by sanctions and diplomatic efforts, however, failed to reverse the annexation, further illustrating the complexity of addressing fabricated minority threats in the modern geopolitical landscape.

Figure 8 Russian soldiers (little green men), without identification marks carry out the orders of President Putin for the annexation of Crimea 2014 – Photo https://neweasterneurope.eu/2020/04/02/crimeas-annexation-six-years-on/

The annexation of the Sudetenland and its comparative analysis with present-day cases show the efficient tactic of fabricating minority threats to justify territorial ambitions. These historical and modern examples highlight the need for vigilance and critical examination of such narratives to prevent the repetition of past mistakes and the erosion of international norms and stability.

Conclusion

At the end of this research, in response of our research question and the raised hypothesis, it becomes necessary to underline the systematic and deliberate actions of Serbia in fabricating the narratives of a threatened Serbian minority in Kosovo. This baseless assertion serves as a pretext for Serbia’s expansionist ambitions under the guise of protecting Serbs abroad. Through this analysis, it has been demonstrated that such claims are not only baseless but are strategically designed to prepare the ground for hybrid warfare tactics against Kosovo. These tactics aim to destabilize the region, utilizing the possibility of using paramilitary or terrorist formations, or even considering a conventional intervention, “if the international circumstances seem favourable”, as the president of Serbia, Aleksandar Vučić, emphasized after a meeting with the president of Azerbaijan weeks ago.

It is critical to note the contrast between the prevalent narrative and the reality on the ground. Serbs in Kosovo, far from being threatened, enjoy protection and rights that are at the top of European standards for minority communities. The democratic institutions of Kosovo, dedicated to the inclusiveness and protection of all citizens, are evidence of respect for civilian freedoms, as well as the highest democratic norms and values. This reality completely contradicts the portrayal presented by Serbian narratives, revealing a manipulative attempt to justify expansionist motives.

Serbia’s interference with the Serbian minority in Kosovo raises deep concerns about democratic principles and human rights. The imposition of a one-party system on the Serbian minority by Serbia not only undermines democratic representation but also contradicts European values based on pluralism and participatory governance. The installation of individuals with criminal backgrounds in positions of influence within the Serbian community in Kosovo further illustrates Serbia’s intimidation and control tactics aimed at silencing moderate voices and suppressing demands for greater democracy and autonomy within the Serbian minority community. As Radio Free Europe stated, Milan Radoicic was committed to threatening the Serbs of Kosovo by suppressing critical voices with intimidation and force, thus making it impossible to articulate any discontent (Cvetković, 2023).

This manipulation and suppression of the Serbian minority in Kosovo by the Serbian authorities, led by President Aleksandar Vučić, requires a strong response. Kosovo must remain vigilant and proactive in dispelling myths from Serbian propaganda. This includes strengthening its information dissemination channels to combat lies and ensure that the international community is well-informed about the realities on the ground. In addition, Kosovo must remain prepared to counter any hostile activity of Serbia, especially in the northern regions, through strategic security measures and international cooperation.

In light of these findings, it is strongly recommended that Kosovo improve and intensify strategic communication, diversifying it from state institutions and civil society partners.

The international community, for its part, should take a more critical stance towards Serbia’s actions and narratives, recognizing the potential threat they pose to peace and security in the Balkans. Furthermore, international actors should support Kosovo in increasing its capabilities to hinder hybrid threats and in building overall defense capacities.

A more proactive approach of Kosovo’s institutions would more effectively oppose the propaganda and information warfare carried out by Serbia and the Russian Federation. The information departments within the main state’s ministries should organize weekly conferences, with updates on the latest events, equipped with the necessary information to dismantle the propaganda against Kosovo.

We also recommend the establishment of a national center where all information warfare attacks are processed in a centralized manner so that they can then be dismantled for the local and foreign public. This center would necessarily be connected with all relevant institutions in the exchange of information. This would make the efforts even easier, by structuring and methodizing the work.

Bibliography

Bechev, D. (2024, January 11). Carnegie Europe. Retrieved from Carnegie Europe: https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/91372

Beljo, A. (1999). Greater Serbia – from Ideology to Aggression. Croatian Information Centre. Cox, J. K. (2002). The History of Serbia. Greenwood .

Cvetković, S. (2023, January 23). Radio Free Europe. Retrieved from Radio Free Europe: https://www.evropaelire.org/a/serbet-vende-pune-millan-radoiciq-/32236189.html

ESI. (2024, February 19). European Stability Initiative. Retrieved from European Stability Initiative: https://www.esiweb.org/publications/invented-pogroms-statistics-lies-and- confusion-kosovo

Giffoni, M. L. (2020, October 1). ISPI. Retrieved from ISPI: https://www.ispionline.it/en/bio/michael-l-giffoni

Haussler, J., & Scheunemann, W. (Directors). (1939). Schicksalswende [Motion Picture]. Huntington, S. P. (2011). The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. Simon &

Schuster.

ICTY. (1999, May 27). International Criminal Tribunal for the Forrmer Yugoslavia. Retrieved from International Criminal Tribunal for the Forrmer Yugoslavia: https://www.icty.org/en/sid/7765

Judah, T. (2008). Kosovo: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford University Press.

Kosovo Online. (2023, October 21). Retrieved from Kosovo Online: https://www.kosovo- online.com/en/news/politics/djuric-washington-conference-we-are-drawing-global- attention-violation-human-rights

Meadow, E. (2022, February 25). Democratic Erosion Consortium. Retrieved from Democratic Erosion Consortium: https://www.democratic-erosion.com/2022/02/25/media-censorship- in-serbia-under-president-vucic/

Nelsson, R. (2021, September 21). The Guardian. Retrieved from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/world/from-the-archive-blog/2018/sep/21/munich- chamberlain-hitler-appeasement-1938

Pesic, V. (1996, April 1). United States Institute of Peace. Retrieved from United States Institute of Peace: https://www.usip.org/publications/1996/04/serbian-nationalism-and-origins- yugoslav-crisis

Plokhii, S. (2022, February 27). Ukrainian Research Institute – Harvard University . Retrieved from Ukrainian Research Institute – Harvard University : https://huri.harvard.edu/news/serhii-plokhii-casus-belli-did-lenin-create-modern-ukraine

Shedd, D., & Stradner, I. (2023, November 7). Foreign Affairs. Retrieved from Foreign Affairs: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/russias-second-front-europe

Tamil, Y. (2019). Why Nationalism. Princeton University Press .

Tomanić, M. (2021). THE SERBIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH during Times of War 1980-2000 and the Wars within it. In M. Tomanić, THE SERBIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH during Times of War 1980-2000 and the Wars within it (p. 77). Lulu.

Zakharova, M. (2024, February 6). The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation.

Retrieved from The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation: https://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/1929828/

Zevelev, I. (2016, August 22). CSIS. Retrieved from Center for Strategic & International Studies: https://www.csis.org/analysis/russian-world-moscows-strategy