Dr. Bleta Brovina

Senior Researcher at Institute for Hybrid Warfare Studies “Octopus”, bleta.brovina@octopusinstitute.org

Abstract

Following the invasion of Crimea by Russia, there has been a significant shift in academic focus towards the study of Ukraine. Russia’s efforts to establish a new warfront in the Western Balkans have drawn attention to the developments in the region. This paper offers a comparative analysis of the narratives put forth by Russia concerning Ukraine and Serbia’s narratives on Kosovo. Both Russia and Serbia have constructed fake narratives that present their geopolitical disputes as issues of historical and national identity and territorial integrity. In the case of Russia, the narratives regarding Ukraine underscore a shared history, the protection of ethnic Russians, while contesting Ukrainian sovereignty. Similarly, Serbia’s narratives about Kosovo emphasize the cultural and historical significance of Kosovo, drawing its fake narrative for Kosovo as integral to Serbian identity and rejecting its independence as illegitimate and imposed by foreign powers. By delving into official discourse and media representations, this study aims to explore three core narratives used as expansionist platforms: historical and national identity narratives, the narrative of victimization and the narratives on the legitimacy of statehood and sovereignty and how these narratives are utilized within domestic and international spheres to gain internal and international support, legitimize policies, and perpetuate a sense of victimhood. The paper contends that although the contexts differ, the strategic deployment of historical grievances, ethnic unity, and anti-Western sentiment forms a common platform in the expansionist approaches of Russia and Serbia.

Keywords: Russia, Ukraine, Serbia, Kosovo, Narratives, Myths.

Cite as: APA style: Brovina, B. (2024). Platforms of expansionism: a comparison of Russia’s narratives for Ukraine and Serbia’s narratives for Kosovo. Octopus Journal: Hybrid Warfare & Strategic Conflicts, 2. https://doi.org/10.69921/wd7k4k92

(CC BY-NC 4.0) This article is licensed to you under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. When you copy and redistribute this paper in full or in part, you need to provide proper attribution to it to ensure that others can later locate this work (and to ensure that others do not accuse you of plagiarism).

1.Introduction

Since the dawn of civilization, the world has been plagued by persistent conflicts and wars as societies vie for interests and resources. Employing narratives and myths as a strategic tool to legitimize these claims has been a common practice. As asserted by Edwards (Edwards, 2015), myths fundamentally function as narratives. Consequently, narratives serve multiple purposes, such as depicting a situation, shaping societal direction, bolstering the identity of specific societies, and serving political aims by establishing legitimacy and mobilizing the masses. These narratives play pivotal roles in shaping the political landscape, and when they propagate false and destructive narratives, they pose a danger to both the audience and others, especially when the truth is disregarded. Various studies have delved into the mechanisms of these narratives and their resulting impacts.

British cognitive psychologist Peter Wason (Wason, 1960) expounded on the confirmation bias theory, elucidating how individuals are inclined to embrace false narratives that align with their pre-existing beliefs. Exploiting this psychological tendency to seek information that confirms existing beliefs, fake narratives thrive while disregarding evidence to the contrary. In “Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media” (Herman & Chomsky, 1988), it is explicated how populations are manipulated, and consent is manufactured through fake narratives, particularly concerning economic, social, and political issues. Furthermore, Maxwell McCombs and Donald Shaw in their work “The agenda-setting function of mass media” (McCombs & Shaw, 1972) shed light on how media focus can provide fertile ground for fake narratives, an essential consideration in political discourse where events and conspiracy theories can gain traction in the public sphere, appearing legitimate despite being false. Of equal significance is the Cultivation Theory put forth by George Gerbner (Gerbner, 1987), originally applied to television, which posits that prolonged exposure to media content can mold an individual’s perception of reality. Similarly, prolonged exposure to fake narratives can engender a cultivated belief in their veracity. Over time, the relentless repetition of a false narrative can lead people to accept it as true, even in absence of evidence. This theory holds relevance across all forms of media.

The significance of these theories and the attention they deserve is particularly heightened at this juncture, given the commencement of the conflict in Ukraine. The war in Ukraine has resulted in a major shift in global geopolitics and continues to exert a substantial impact on the Western Balkans. Despite the fact that the conflict has not extended into the Western Balkans, the region has not been immune to hybrid warfare tactics, jeopardizing the fragile peace in the area. These tactics encompass a range of strategies, such as disseminating false narratives about neighboring countries and, in the most extreme instance, the aggressive actions of Serbian groups affiliated with the Serbian state in Banjska, with the ultimate goal of declaring the northern part of the Republic of Kosovo as autonomous, thereby endangering Kosovo’s territorial integrity. Musliu and Elshani (Musliu & Elshani, 2023) have provided further analysis of Serbian and Russian propaganda in Kosovo.

The dissemination of false narratives has been accompanied by the proliferation of accounts portraying neighboring countries and ethnic minorities as adversaries, along with false narratives depicting ethnic minorities as being at risk from their host neighboring country. Furthermore, this has included the glorification of past wars, war criminals, and the promotion of other false narratives, all of which has contributed to heightening fear domestically and within neighboring countries. The utilization of these forms of hybrid warfare tactics has been observed in Russia’s actions in Ukraine and Serbia’s actions in Kosovo. Russia extensively employs state-controlled media to reinforce its false narratives about Ukraine. Similarly, Serbia utilizes media channels to advance its narrative about Kosovo, both domestically and internationally, although it lacks the same level of global media influence as Russia. Given that Kosovo is one of the most pro-American countries, which leaves no space for sentiment aligned with Russia, the spread of Russia’s false narratives in Kosovo is facilitated through Serbia and its media as a proxy for Russia (See: Musliu & Elshani, 2023).

2.Methodology

This research paper conducts a comparative analysis of the narratives presented by Russia on Ukraine and by Serbia on Kosovo. It explores the commonalities, differences, and parallels in these narratives, focusing on historical perspectives, national identity, protection of ethnic and linguistic minorities, territorial claims, statehood legitimacy, sovereignty, Western influence, and victimization narratives. The study adopts a qualitative approach, specifically focusing on smaller-N studies research. It aims to shed light on the core activities of disseminating misinformation, as executed by Russia regarding Ukraine and Serbia regarding Kosovo. The selected countries for comparison, Russia and Serbia, are both recognized as aggressor nations with territorial ambitions towards Ukraine and Kosovo, demonstrating similar hostile behaviors towards their respective neighboring countries. The discourse employed by Serbia towards Kosovo mirrors that of Russia towards Ukraine, leading to the perception that Serbia is adopting a similar approach to Russia in its interactions with neighboring countries.

The paper conducts official discourse analysis focusing on past and current discourse, with particular attention, but not limited, to the narratives of three leaders, from the aggressor countries: Vladimir Putin, Slobodan Milosevic, and Aleksander Vucic. The choice to focus on these leaders stems from their use of narratives to justify aggression toward other territories. Putin’s narratives concerning Ukraine serve to justify Russian aggression, akin to Milosevic’s use of narratives to justify aggression towards Kosovo and genocidal projects in Balkans. Furthermore, Vucic, as the former minister of propaganda and current President of Serbia, continues this legacy. The analysis utilizes direct observation to cover contemporary events.

Speeches by the leaders, interviews, scholarly articles, reports, commentaries, newspaper accounts, public statements by officials, and other printed sources form the basis for interpreting the data. Any gaps in available material are addressed through examination of annual reports from civil society organizations and international organizations.

It is important to emphasize that since the paper is focused in the past and current period of time, the state’s official name of Russia, Serbia, Ukraine and Kosovo has changed over time. Being aware of these changes, for practical reasons Russia, Serbia, Ukraine and Kosovo will be used as names to indicate the given territories.

Furthermore, it is crucial to clarify that references to the spread of fake narratives by Russia and Serbia do not encompass all segments of these societies. The reference primarily pertains to the governments, the orthodox church, and academic structures under government control, which play a central role in disseminating these narratives (Tomaniq, 2001). Notably, not all segments of these societies are involved in spreading fake narratives. Despite being a minority, certain actors in civil societies within these countries deserve recognition for their efforts in upholding truth within hostile environments under the authoritarian regimes of Russia and Serbia.

The following presents a comparative analysis of the fundamental aspects of Russia’s narratives on Ukraine and Serbia’s narratives on Kosovo, across three dimensions: historical and national identity narratives, the narratives of victimization, and the narratives on legitimacy of statehood and sovereignty.

3. Russia’s and Serbia’s fake narratives in the function of expansionism

3.1. Historical and national identity narratives

Prior to the commencement of the war, Ukrainian history had not received adequate attention within the academic realm of Western democracies, including those in the United States. Ukrainian historians took it upon themselves to diligently construct a comprehensive narrative of Ukrainian history throughout the nineteenth century, emphasizing the distinctiveness of Ukrainian history from that of Russia. Mykhailo Hrushevsky, a prominent Ukrainian historian, ardently advocated for the Ukrainian narrative in his seminal work “Istorija Ukrajiny-Rusy” published in 1898. In stark contrast, Russian historical narratives assert that Ukrainian history is an integral part of Russian history, attributing their common origin to Kyivan Rus’, a principality established in the 9th century and considering Ukraine as an integral part of the “Russian World” (Russkiy Mir). Russia further utilized religion as a tool to label Ukrainians as “orthodox brothers and sisters”, employing this narrative to expand their influence into territories where orthodox beliefs were practiced. Despite the shared orthodox belief, it is argued that the Ukrainian orthodox church possesses distinct characteristics setting it apart from the Russian orthodox church. Presently, Russia’s efforts to eradicate these unique traits of the Ukrainian orthodox church and replace them with Russian orthodox characteristics are perceived as attempts to erode the distinct religious identity of Ukraine. From the nineteenth century until the twentieth century Russia has considered Ukraine as “Little Russia (Malorossija)” explains Iryna Synelnyk, PhD, an expert in History from the Institute of History of Ukraine (Synelnyk, 2024). According to IPI Report Observatory, since the 24thof February 2022, Russia has destroyed 351 protected Ukrainian cultural heritage targeted intentionally to erase Ukrainian distinct cultural and historical identity(Observatory, 2024).

Historically, Ukraine’s territory has been subjected to various ruling powers over time, influencing the country’s cultural landscape. Russia’s narrative contends that Ukrainians are essentially estranged Russians ruled by foreign powers, and the Ukrainian language is merely a dialect of Russian. However, this narrative overlooks significant historical evidence, such as the distinct nature of the Ukrainian language during specific periods, such as when the language spoken by Zaporizhian Cossacks during the 17th century was unintelligible to Russians. Ukrainian historians highlight figures like Bohdan Khmelnytsky, a Cossack who played a pivotal role in the efforts to establish a sovereign Ukrainian state during the same century, with Cossack elements also resonating in the national anthem, exemplifying their significant contribution to Ukrainian national identity (Mick, 2023).

From Putin’s perspective, modern Ukraine was established by Communist Russia. He perceives Russia and Ukraine as unified people, sharing a common historical and spiritual space. Putin emphasizes that his beliefs are not merely influenced by the contemporary political context but are deeply held and reiterated on several occasions. He regards the division between Russia and Ukraine as a regrettable and tragic occurrence (Putin, Kremlin, 2021).

In medieval times, Ukraine was part of first one and then another European power center, coming under the rule of one country, then another. But the vision of uniting both the western and eastern parts of Rus’, the state that had its beginnings here in Kiev (. .) always lived on in the east and in the west, wherever our people lived. The unity of east and west changed the lives of Ukraine’s population and its elite for the better, as everyone knows. (. . .) Let me say again that we will respect whatever choice our Ukrainian partners, friends and brothers make. The question is only one of how we go about agreeing on working together under absolutely equal, transparent and clear conditions (Putin, Kremlin, 2013).

The following is an analysis of Vladimir Putin’s speech in Kyiv on July 27, 2013, and its implications for Russia’s actions in Ukraine. Despite Putin’s professed respect for the Ukrainian people’s choices, Russia’s subsequent invasion of Crimea in 2014 andthe ongoing war that intensified on February 24, 2022, proves the contrary, thatRussiadoes not respectUkrainian autonomy and sovereignty. Instead of honoring Ukrainian identity, Russia’s actions suggest a goal of territorial expansion and erasure of Ukrainian cultural and national heritage.

Similarly, Serbia’s narratives regarding Kosovo aim to justify territorial claims by portraying Kosovo Albanians as a distinct nation that has migrated from Albania and seized Serbian land. These fake narratives not only serve to bolster political legitimacy but also fuel nationalism and shape Serbian national identity. The historical debate between Serbs and Albanians revolves around claims of primacy in populating the region, with Albanians asserting autochthony supported by archaeological evidence, such as the monumental inscription discovered in Ulpiana. This inscription, associated with Emperor Justinian, suggests early connections between Albanian territories and the Roman Empire, bolstering the argument for Albanian continuity and distinctiveness. An examination of language and historical evidence supports the view that Illyrians are predecessors of the Albanian people.Malcom argues that, leaving aside Greeks, Albanians are the only nation in the Balkans with a clear pre-roman civilization origin, from pre-roman societies, in this case from Illyriansand Dardans as an Illyrian branch (Malcom, 2024).Recent discoveries further corroborateNoel Malcom’s scholarly findings that Christian influences reached Albanian territories during the early stages of the Roman Empire. The linguistic similarities and shared elements between the Illyrian, Latin, and Albanian languages provide compelling evidence supporting the argument that the Illyrians were the precursors of the Albanian people (Malcom, Kosova. Nje histori e shkurter, 2019).

In contrast to these arguments, Serbia promotes its own narrative, which asserts that Kosovo’s myth originated in Serbia. Although Serbia acknowledges its arrival in Albanian-inhabited territories in the 6th century A.D(Schmitt, 2012), it disputes the claims made by Albanians: that they were the original inhabitants, that they are indigenous to the territories, and that Serbs invaded their land. Serbia’s narratives about Kosovo primarily focus on the Middle Ages. According to this narrative, Kosovo was inhabited by Serbs during that period, but the population composition changed after the arrival of the Ottomans. Serbia has constructed a narrative suggesting that Kosovo Albanians originated from Albania and settled in Kosovo after arriving from Albania. The myth of Kosovo is rooted in the historical events of the Battle of Kosovo, which took place on June 28, 1389, between the Ottoman forces led by Sultan Murad and the joint forces of different ethnic groups led by Knez Lazar. Historical evidence indicates that the leaders of both sides were found dead, and there was no clear winner of the battle, resulting in a stalemate. However, Serbia has utilized this event to construct a narrative depicting the battle of Kosovo as a definitive Ottoman victory, but a spiritual victory for Serbs, further reinforcing the narrative of victimization (Anzulovic, 2017).

Notably, the first written version of Serbia’s myth concerning the Battle of Kosovo emerged with the Serbian national movement no earlier than the middle of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century (Bieber, 2002). According to this myth, prophet Elijah appeared before Knez Lazar, offering the choice between the destruction of the army to win the heavens or the defeat of the Ottoman army to prevent the spread of Islam and win the earthly empire. The Serbian myth suggests that Knez Lazar chose the heavenly empire, leading to the defeat of his army by theOttomans(Bieber, 2002; Surroi, 2018; Anzulovic, 2017).

600 years following the battle of Kosovo, in his renowned address at Gazimestan on the 28th of June 1989, Slobodan Milosevic utilized this narrative to bolster Serbian nationalism, unite Serbs, and solidify his political legacy by depicting Serbs as victims. This event marked the onset of Serbian oppression over Kosovo Albanians, following a period of relative peace in Yugoslavia, eventually culminating in violent conflicts and the disintegration of Yugoslavia. By emphasizing the disunity of Serbs, Milosevic indicated that the truth regarding the battle of Kosovo was no longer of paramount importance.

Today, it is difficult to say what is the historical truth about the Battle of Kosovo and what is legend. (Today) this is no longer important. Oppressed by pain and filled with hope, the people (used to suffer and forget), as, after all, all people in the world do, and [word indistinct] and glorified heroism. Therefore, it is difficult to say today whether the Battle of Kosovo was a defeat or a victory for the Serbian people, whether thanks to it we fell into slavery or whether thanks to it we [word indistinct] in this slavery. The answers to those questions will be constantly sought by science and the people. What has been certain through all the centuries until our time today is that disharmony struck Kosovo 600 years ago(Milosevic, 1989).

By disregarding historical facts and the current realities on the ground, Milosevic has adeptly utilized these narratives to bolster Serbian nationalism, construct Serbian identity, cement political legitimacy, and leverage these narratives to sway and rationalize the expansionist policies to both the Serbian population and others while portraying Serbs as victims. This further perpetuates the narrative of victimization.

3.2. The narrative of victimization

The victimhood narrative is a strategic tool employed by expansionist countries to justify their actions and cultivate nationalism. Both Russia and Serbia utilize this narrative to position themselves as victims within the international community and among their own population. Their victimization narratives are based on two main grounds: the first being the victimization of their ethnic minorities within the host state, such as Russians in Ukraine and Serbs in Kosovo, and the second being the portrayal of Russia and Serbia as victims in their interactions with the West.

Russia often presents itself as a guardian of ethnic Russians and Russian speakers, portraying them as victims of Ukrainian nationalism. This narrative includes allegations of discrimination, persecution, and even genocide against Russian-speaking populations in Ukraine, particularly in Crimea and Donbas. Furthermore, the narrative suggests that the Ukrainian government is under the control of nationalist extremists who oppress Russian-speaking minorities, particularly in Eastern Ukraine and Crimea. In addition to emphasizing the unity of Ukrainians and Russians, Russia accuses Western countries of manipulating the concept of a separate Ukrainian identity and portrays Ukraine’s independence as artificial, instigated by external Western forces.

Russia’s narrative emphasizes the historical interconnectedness of the Russian and Ukrainian peoples, asserting that Ukraine is an indispensable part of the “Russian World” due to shared history, culture, and religion. Russia presents Ukraine’s independence as an artificial construct instigated by external Western influences, positioning Russia as a victim of Western democracies. However, Russia overlooks the historical recognition of Ukrainians as a distinct nation by the Soviet Union, particularly by the Bolsheviks, separate from the Russian nation. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, both Russia and the international community acknowledged Ukrainian independence. Putin laments this historical event as a tragedy, attributing it to Russia’s own errors and accusing the West of perpetually aiming to divide “one people” and incite conflict between them.

But these are also the result of deliberate efforts by those forces that have always sought to undermine our unity. The formula they apply has been known from time immemorial–divide and rule. There is nothing new here. Hence the attempts to play on the ”national question“ and sow discord among people, the overarching goal being to divide and then top it the parts of a single people against one another(Putin, Kremlin, 2021)

Russia presents the West, particularly the United States and NATO, as the main catalysts of the crisis in Ukraine, alleging their involvement in orchestrating a coup in 2014 and seeking to align Ukraine with Euro-Atlantic influences while distancing it from Russia. According to Russia, the 2014 Euromaidan protests were a Western-backed coup, and Ukraine’s association with Western institutions such as the EU and NATO is viewed as a direct threat. Russia tends to depict the Ukrainian government as a puppet of Western powers, particularly the United States and NATO, accusing the West of aiming to detach Ukraine from Russia’s sphere of influence. Thus, Russia portrays itself as a victim of Western democratic policies and justifies its aggression towards Ukraine as actions to protect Russia and the Russian-speaking population in Ukraine. However, this narrative is vastly disconnected from reality and Russia’s true intentions, which revolve around expansionism, the erosion of Ukrainian culture and identity, the destabilization of neighboring countries, and the pursuit of the “Russian World”. Similarly, like Russia, Serbia harbors expansionist ambitions towards its neighboring countries, especially Kosovo, aiming to establish the “Serbian World”or “Great Serbia”.

Drawing on the same myth, Serbia has invoked the Kosovo myth once more to perpetuate and construct a narrative of victimhood. The Serbian narrative revolves around Kosovo as the historical and cultural epicenter of the Serbian nation, particularly due to its significance as the location of the medieval Battle of Kosovo in 1389(Di Lellio, 2009). Serbia perceives Kosovo as its sacred territory, inseparable from Serbian identity, irrespective of its ethnic and religious composition. Serbia underscores the narrative of the imperative to safeguard Serbian cultural and religious heritage sites in Kosovo. Analogous to Russia, Serbia accentuates the plight of the Serbian minority in Kosovo, depicting them as targets of the Albanian-led government and as a menace to the safety and rights of Serbs. Serbia wholly disregards the prevailing realities. In accordance with Ahtisaari’s Plan (Ahtisaari, 2008), enshrined in the Constitution of Kosovo (Assembly, 2008), Serbian minorities possess the most comprehensive minority rights in Europe and beyond. Through Lista Srpska, a political party controlled by Vucic, Serbia consistently exploits the rights of Kosovo Serbs with the intention of undermining Kosovo’s institutions. Acknowledging this peril, in an interview given to a TV broadcaster in Prishtina, Ahtisaari himself has declared that he would not grant the Serbian minority all these rights. But the outcome of his Plan is an effort to secure the acceptance of his Plan by Russia and Serbia (Ahtisaari, Conflict Resolution: The Case of Kosovo, 2008). The Serbian narrative frequently underscores the necessity of safeguarding Serbs and Serbian Orthodox heritage sites in Kosovo. Nonetheless, Serbia wholly disregards the fact that these same Orthodox Churches were utilized and manipulated by the Serbian paramilitary groups associated with the Serbian state to conceal weapons, which were subsequently employed during the “Banjska attack” orchestrated by the Serbian state (Musliu, Haxhixhemajli, & Elshani, Serbian terrorist attack in Banjska and regional and geopolitical implication, 2023).

Serbian narratives have highlighted disunity as the root cause of the suffering of Serbs. Similarly to Putin, Milosevic also attributed the suffering of Serbs to disunity, placing blame on Serbian leaders for the hardships experienced by the Serbs. Milosevic emphasized the disunity of Yugoslavia and expressed his determination to take actions to prevent further suffering of the Serbian people, referring to Croatian and Slovenian nationalism as a ‘crisis’ (Milosevic, 1989).

The concessions that many Serbian leaders made at the expense of their people could not be accepted historically and ethically by any nation in the world, especially because the Serbs have never in the whole of their history conquered and exploited others. Their national and historical being has been liberational throughout the whole of history and through two world wars, as it is today (Milosevic, 1989).

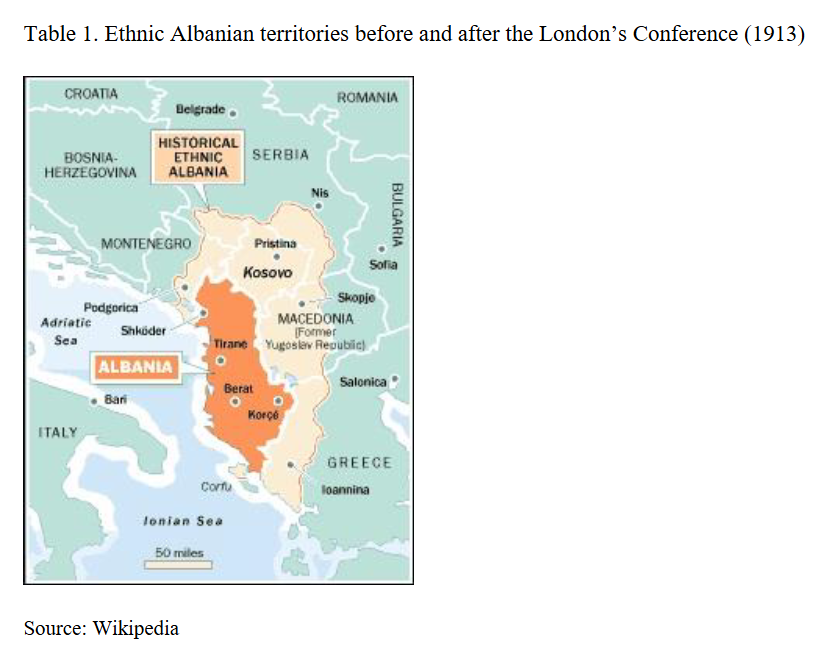

Historical data show the opposite to what Milosevic has propagated. During the London’s Conference in 1913 more than 40% of the ethnic Albanian territories were left outside the National border of Albania. The ethnic Albanian territories given to Serbia have experienced ethnic cleansing (Jubani, et al., 1996).

Slobodan Milosevic’s measures propagated ‘to stop the suffering of serbs” resulted with bloody wars in former countries of ex-Yugoslavia,in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo generating130.000 deaths, 2.4millionrefugees andadditional 2millioninternally displaced persons(Watkins, 2003).The aftermath also left profound psychological trauma, and inflicted severe cultural, historical, and economic damage, marking it as one of the most brutal conflicts in Europe since World War II. Milošević was indicted for crimes during the Kosovo war, by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) (ICTY, 2006), while the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued arrest warrants for Vladimir Putin on 17.03.2023, following an investigation of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide (ICC, 2023).

The same fake narratives on victimization Russia continues to spread in synchronization with Serbia drawing parallels between Ukraine and Kosovo. Recently Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov declared:

The persecution of Serbs from Kosovo is similar to the Nazi persecution of the Russian population from the territory of Donbas, which was carried out by the Ukrainian authorities. They said that without Ukraine, there would be no civilization in Crimea and Donbas, and in the 30s of the last century, the elite race declared that only it could bring civilization to Europe. Ethnic cleansing is pure as tears. Also, thank God, without serious military conflicts, they are trying to expel the Serbs from Kosovo(Lavrov, 2024).

Lavrov ignores the fact that after the investigations, Putin is the one indicted for war crimes from ICC and not Zelensky. While in the Northen Kosovo the government took actions to close Serbia’s illegal parallel institutions in attempt to establish the rule of law in the Northen Kosovo in accordance with Kosovo’s Constitution (2008). The Constitution provides one of the most extensive models of ethnic minorities’ rights protections in Europe, giving Kosovo’s Serbas wide range of privileges within Kosovo. In a Conference held just the other day, Vucic presented seven requests and five measures for Kosovo, all these in the function of the narrative of victimhood. Vucic has requested the return of Serbs who have boycotted and resigned from the Police and Judiciary institutions, without giving at least an explanation why did he force the same Serbs to resign in 2022(Tershani, 2024). On the other hand, he announced that special judicial panels and a special prosecutor’s office will be established in Serbia which:

… will investigate and prosecute criminal and illegal acts committed by officials who carry out actions violating human rights against the Serbian population in Kosovo and Metohija. This will also include individuals of Serbian nationality who, on behalf of and for the benefit of the Albanian secret police, are conducting the persecution of Serbian people in the worst possible ways, participating in the expulsion of our population (Vucic, 2024).

On one side Vucic calls the return of resigned Serbis in Kosovo’s institutions, on the other side he threats the very same Serbs to be prosecuted if they collaborate with the very same institutions.

Finally, he denied the Banjska attack to be a terrorist act, despite the fact that now there is an indictment from the Special Prosecution and there is an international report which was handled to NATO and Kosovo’s Institutions indicating that the Banjska attack was orchestrated by Serbia.

In the latest report Robert Lansing Institute for Global Threats and Democracies Studies warns:

Sonja Biserko, chair of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia, Nenad Čanak, former leader of the center-left League of Social Democrats of Vojvodina, and Mark Baskin, a senior adviser from the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, have raised concerns about reports that houses and apartments are being built for Kosovo Serbs, particularly those from the northern region, in Serbia’s Sandžak region. They urged the Kosovo government to verify these reports. The indicators shows that Vucic might be orchestrating a plan involving the relocation of northern Kosovo Serbs to Serbia. In his current political predicament, Vucic could fabricate an excuse to accuse Kosovo of ethnic cleansing against the Serbs, which could lead to a troubling humanitarian situation and severe consequences for Kosovo on the international stage (Institute, 2024)

This is another maneuver from Vucic to construct and impose fake narratives of victimhood to its population and to the international community, which is an attempt to destabilize Kosovo.

3.3. The narratives on the legitimacy of statehood and sovereignty

Russia’s challenge to the legitimacy of Ukraine’s sovereignty, particularly in regard to Russian speaking areas, Crimea and Donbas, raises significant geopolitical concerns in the international level. The annexation of Crimea in 2014 was justified by Russia through a disputed referendum, which it asserts reflected the desires of the local population. Furthermore, Russia’s backing of separatist movements in Eastern Ukraine adds complexity to the situation. Russia disputes the legality of Ukraine’s current borders, particularly following the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the conflict in Eastern Ukraine. By emphasizing the popular referendum in Crimea as grounds for annexation, Russia presents its involvement in Eastern Ukraine as a defense of Russian speakers and ethnic Russians against Ukrainian aggression. However, it selectively applies international law, justifying the annexation of Crimea based on the principle of self-determination while rejecting similar arguments when applied to other regions. Addressing the Russian parliament after the referendum to join the Russian Federation in Crimea in 2014, Vladimir Putin compared Crimea with Kosovo accusing the West.

In a situation absolutely the same as the one in Crimea they [the West] recognized Kosovo’s secession from Serbia as legitimate, arguing that no permission from a country’s central authority for a unilateral declaration of independence is necessary (Putin, 2014).

Putin has drowned parallels between Crimea and Kosovo, ignoring the fact that Kosovo’s independence was a sui generis case, the last legal step of the dissolution of Yugoslavia and there is a long checklist of the differences between Crimea and Kosovo. The Independence of Kosovo was declared in close coordination with Western democracies, after internationally verified facts that Serbia committed ethnic cleansing in Kosovo, and the failure of Western democracies to convince Serbia for several proposed solutions for Kosovo’s case (see: Weller, 2009). The International Court of Justice has found that the declaration of independence of Kosovo did not violate the international law. Nevertheless, Putin has used Kosovo’s case to move forward with his expansionist intentions toward Ukraine and its neighboring countries.

Russia’s actions in Ukraine are part of a broader strategy to maintain influence in its surrounding region and impede further NATO expansion. Notably, the control over Crimea secures Russia’s strategic interests in the Black Sea. The conflict in Ukraine is indicative of a larger geopolitical struggle—Russia aims to maintain influence in the post-Soviet space and prevent NATO expansion. Unfortunately, Russia’s involvement in Ukraine has led to significant destabilization, fueling the ongoing conflict in Eastern Ukraine and contributing to tensions in the broader region. Moreover, the annexation of Crimea has set a precedent for future territorial disputes.

Serbia’s perspective on Kosovo aligns with Russia’s position, as both countries consider Kosovo to be a contested entity, resulting from external influence, particularly from the U.S. and the EU(see: Musliu & Kuci, Octopus Institute, 2024). Serbia firmly asserts that Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence in 2008 violates international law, emphasizing the importance of respecting Serbia’s territorial integrity. Similar as Russia, after the Banjska attack, it is confirmed that in addition to diplomatic means, Serbia uses the armed forces to reclaim Kosovo (see: Musliu, Haxhixhemajli, & Elshani, Serbian terrorist attack in Banjska and regional and geopolitical implication, 2023).

Serbia’s refusal to acknowledge Kosovo’s independence is also motivated by the desire to preserve its influence in the region and moving further with its expansionist intentions in the region. Additionally, Serbia’s stance on Kosovo is in line with Russia’s geostrategic goals, to have access in Adriatic Sea. Since the Albanian speaking territories are characterized with profound pro Americanism and negative sentiments for Russia, Russia calculates to extent its influence through its proxy Serbia and Serb minorities in Kosovo controlled by Vucic, such as Lista Srpska. This ongoing dispute over Kosovo’s status not only impacts Serbia’s relationship with neighboring countries but also has implications for the regional integration processes in the Euro-Atlantic structures, undermining of which go in Russia’s and Serbia’s best interests and their geostrategic goals in the Western Balkans.

Conclusions

The comparison of Russia’s and Serbia’s narratives concerning Ukraine and Kosovo, reveals substantial parallels in the deployment of historical, cultural, and political rhetoric to assert territorial claims and influence public perception. In both cases, national identity, historical grievances, the defense of ethnic kin and anti-Western narratives are central in justifying opposition to the sovereignty of Ukraine and Kosovo. While there is a significant number of Russia’s and Serbia’s fake narratives concerning Ukraine and Kosovo, three principal narratives are used as expansionist platforms: historical and national identity narratives, the narrative of victimization and the narratives on the legitimacy of statehood and sovereignty.

These narratives not only contribute to domestic identity construction but also delegitimize the independence of Ukraine and Kosovo on the international stage, strengthening the perception of these disputes as struggles against external forces, notably the West. Russia’s positioning on Ukraine underscores the historical unity of the two nations, the safeguarding of Russian-speaking populations, and the contention that Ukraine’s independence is an artificial and Western-imposed construct. Similarly, Serbia’s perspective on Kosovo depicts it as the core of Serbian identity and history. Unlike Russia’s narrative considering Ukrainian “as one people”, due to the differences in the language, religion and traditions, Serbia has built the fake narrative that Kosovo Albanians have arrived in Kosovo from Albania, ignoring internationally discovered historical facts, that Kosovo Albanians are autochthonous in the given lands. Serbia rejects Kosovo’s independence as a breach of international law and Serbian territorial integrity, without taking into consideration the decision of ICJ that Kosovo’s declaration of independence did not violate the International Law, and it is recognized by 117states (KosovoThanksYou, 2024). Narratives employ similar strategies, including appeals to victimhood, the utilization of fake historical narratives, and the portrayal of NATO and Western actors as enemies. These discourses act as internal tools for increasing nationalism and political cohesion, and as external tools to move their expansionist intentions forward, while seeking empathy from international allies. Nonetheless, they also impede reconciliation efforts, fuel ongoing conflict, and fortify divisions regionally and globally. The comparison of these two cases underlines the broader repercussions of utilizing historical and ethnic narratives by Russia and Serbia to navigate contemporary geopolitical challenges. By framing territorial disputes in the context of cultural heritage, historical justice, and ethnic solidarity, Russia and Serbia perpetuate long-standing conflicts and move forward with their expansionist strategies. While Russia and Serbia both utilize historical and ethnic narratives to validate their positions on Ukraine and Kosovo respectively, Russia’s approach is more forceful, involving direct military intervention and a broader geopolitical confrontation with the West. Similarly, Serbia’s approach during the 90-ties was forceful not just towards Kosovo, but its neighboring countries of former Yugoslavia. In the current days, Serbia’s narratives remind us of bad old times narratives before the war. The conflict in Ukraine has not directly affected the Western Balkans. However, this should not lead the West to develop a false sense of no danger. These narratives hold significant implications for regional stability and international relations, reflecting broader geopolitical struggles. While the geopolitical contexts of Russia-Ukraine and Serbia-Kosovo differ, the strategic deployment of historical narratives to assert territorial claims and resist the Western influence is a common feature. Understanding these narratives is crucial for international actors seeking to mediate conflicts in both Ukraine and Kosovo, as they hide Russia’s and Serbia’s real expansionist intentions.

References

Ahtisaari, M. (2008). Comprehensive Proposal for Kosovo’s Status Settlement. Retrieved from Security Council: https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/Kosovo%20S2007%20168.pdf

Ahtisaari, M. (2008). Conflict Resolution: The Case of Kosovo. Irish Studies in International Affairs, 183-187.

Anzulovic, B. (2017). Serbia Hyjnore. Nga Miti ne Gjenocid (Heavenly Serbia. From Myth to Genocide). Prishtina: Koha.

Assembly.(2008). Retrieved from Assembly. Republic of Kosovo: http://old.kuvendikosoves.org/?cid=2,1058

Bieber, F. (2002). Nationalist Mobilization and Stories od Serb Suffering. Rethinking History, 95-110.

Di Lellio, A. (2009). The Batlle of Kosovo 1389. A Albanian Epic.I.B. Tauris (July 15, 2009).

Edwards, J. A. (2015). Bringing in Earthly Redemption: Slobodan Milosevic and the National Myth of Kosovo. Advances in the History of Rhetoric, S187-S204.

Gerbner, G. (1987). Science on Televison: How It Affects Public Conceptions. Issues in Science and Technology, 109-115.

Herman, E. S., & Chomsky, N. (1988). manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. London: The Bodley Head 2008.

ICC. (2023, 03 17). Situation in Ukraine: ICC judges issue arrest warrants against Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin and Maria Alekseyevna Lvova-Belova. Retrieved from ICC: https://www.icc-cpi.int/news/situation-ukraine-icc-judges-issue-arrest-warrants-against-vladimir-vladimirovich-putin-andICTY. (2006). Slobodan Milosevic. Retrieved from ICTY: https://www.icty.org/x/cases/slobodan_milosevic/cis/en/cis_milosevic_slobodan_en.pdfInstitute, R. L.(2024, 09 13). Robert Lansing Institute. Retrieved from Robert Lansing Institute: https://lansinginstitute.org/2024/09/13/vucics-maneuver-to-stay-with-and-against-the-west-by-destabilizing-kosovo/

Jubani, B., Xhufi, P., Bicoku, K., Duka, F., Myzyri, H., Belegu, M., . . . Sadikaj, D. (1996). Historia e popullit shqiptar.Prishtina: Enti i teksteve dhe mjeteve mesimore i Kosoves.

KosovoThanksYou. (2024, 09). Kosovo Thanks You. Retrieved from Kosovo Thanks You: https://www.kosovothanksyou.com/

Lavrov. (2024, 09 12). Voxnews. Retrieved from Voxnews: https://www.voxnews.al/english/kosovabota/serbet-po-debohen-nga-kosova-lavrov-ne-mbeshtetje-te-beogradit-krahas-i74153

Malcom, N. (2019). Kosova. Nje histori e shkurter.Prishtina: Koha.

Malcom, N. (2024). Malcolm, historiani që i tregoi botës historinë e Kosovës. Retrieved 09 05, 2024, from Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=41-0WUAdf5A

McCombs, M., & Shaw, D. (1972). The agenda-setting Fuction of Mass Media. Public Opinion Quarterly, Volume 36, Issue 2, 176-187.

Mick, C. (2023). The Fight for the Past: Contested Heritage and the Russian Invasion of Ukraine. The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice, 135-153.

Milosevic. (1989, 06 28). Historical and Investigative Research. Retrieved from Milosevic’s 1989 speech in Gazimestan, the Field of Black Birds (or Kosovo Polje): https://www.hirhome.com/yugo/bbc_milosevic.htm

Musliu, A., & Elshani, T. (2023, 12). Serbian and Russian Propaganda in Kosovo. Prishtina, Republic of Kosovo: Institute for hybrid Warfare Studies”Octopus”.

Musliu, A., & Kuci, G. (2024, 09 24). Scenarios after Banjska and the russo-serbian hybrid warfare in Kosovo. Retrieved fromOctopus Institute: https://octopusinstitute.org/scenarios-after-banjska-and-the-russo-serbian-hybrid-warfare-in-kosovo/.

Musliu, A., Haxhixhemajli, A., & Elshani, T. (2023, 10 11). Serbian terrorist attack in Banjska and regional and geopolitical implication. Serbian terrorist attack in Banjska and regional and geopolitical implication. Prishtina, Republic of Kosovo: Institute for Hybrid Warfare Studies “Octopus”.

Observatory, I. G. (2024, 04 24). When Protectors Become Perpetrators: The Complexity of State Destruction of Cultural Heritage. Retrieved from The Global Observatory: https://theglobalobservatory.org/2024/04/when-protectors-become-perpetrators-the-complexity-of-state-destruction-of-cultural-heritage/

Putin. (2014, 03 18). Putin Says Kosovo Precedent Justifies Crimea Secession. Retrieved from Balkan Insight: https://balkaninsight.com/2014/03/18/crimea-secession-just-like-kosovo-putin/

Putin, V. (2013, 07 27). Kremlin. Retrieved 09 02, 2024, from Orthodox-Slavic Values: The Foundation of Ukraine’s Civilisational Choice Conference: http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/18961

Putin, V. (2021, 07 21). Kremlin. Retrieved 09 02, 2024, from Article by Vladimir Putin” On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians “: http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/66181

Schmitt, O. J. (2012). Kosova. Histori e shkurter e nje treve qedrore balkanike.Prishtine: Koha.

Surroi, V. (2018). Machiatos cow.Prishtina: Koha.

Synelnyk, I. (2024). About Ukraine. (B. Brovina, Interviewer)

Tershani, Q. (2024, 09 14). KlanKosova. Retrieved from KlanKosova: https://klankosova.tv/vuciqit-i-deshtoi-plani-tani-do-kthimin-e-serbeve-te-dorehequr/

Tomaniq, M. (2001). Srpska crkva u ratu i ratovi u njoj.Medijska knjizara Krug.

UNMIK. (2024). UN Resolution 1244. Retrieved from UNMIK: https://unmik.unmissions.org/united-nations-resolution-1244

Vucic. (2024, 0913). Kosovo online. Retrieved from Kosovo online: https://www.kosovo-online.com/en/news/politics/vucic-necessary-return-status-quo-ante-13-9-2024

Wason, P. (1960). On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task. Quarterly Journal. Quarterly Journal, 12-40.

Watkins, C. S. (2003). The Balkans. Nova Publishers.

Weller, M. (2009). Contested Statehood: The international Administration of Kosovo’s struggle for Independence.Oxford University Press.

Dr. Bleta Brovina holds a PhD in International Studies from the School of International Studies (University of Trento-Italy) with a focus on Western Balkans, power-sharing, constitutional law and minorities’ rights. She has aM.sc in Law from the University of Prishtina. She started her legal activity at a law firm in Prishtina. Bleta has worked as a legal officer in a bank, in the United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) -European Union Pillar IV for economic development and at the Faculty of Law, University of Prishtina. She was a Visiting Research Fellow at Centre for Southeast European Studies, University of Graz (Austria) and at Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law in Heidelberg (Germany). Dr. Brovina is a Lecturer at the University of Business and Technology (UBT) in Prishtina. She has joined the Institute for Hybrid Warfare Studies “Octopus” in 2024.

Her research interests include state building, Western Balkans, power-sharing, constitutional transformation in South-Eastern Europe, minorities’ rights, European integration, peace building, rule of law, financial law, security and hybrid warfare.