Dr. Gurakuç Kuçi

Senior Researcher at Institute for Hybrid Warfare Studies “OCTOPUS”

gurakuq.kuqi@octopusinstitute.org

Abstract

This paper examines Russia’s hybrid warfare tactics against the Western Balkans, focusing on using direct and indirect methods to exert influence in the region. The study delves into Russia’s strategic use of media manipulation, cyberattacks, and disinformation campaigns, alongside its employment of proxy state and non-state actors such as Serbia, Republika Srpska, and the Serbian Orthodox Church. Leveraging historical, cultural, and religious ties, Russia seeks to destabilize the Western Balkans and prevent closer integration with NATO and the European Union. Special attention is given to the geopolitics of elections, where Russia manipulates electoral processes in countries like Montenegro and North Macedonia to favor pro-Russian or anti-Western political forces. By analyzing key case studies, this paper explores how Russian hybrid warfare exploits regional vulnerabilities—such as ethnic divisions and weak political institutions—while employing tactics of soft power and military cooperation. The findings indicate that Russia’s hybrid warfare, including electoral manipulation, poses a significant threat to regional stability and international security, underscoring the need for strengthened Western engagement to counter Russian influence. This study offers critical insights into the evolving nature of hybrid warfare and its implications for the geopolitical landscape of Southeast Europe.

Keywords: Russia, Serbia, election geopolitics, methods of hybrid warfare, Western Balkan, proxy, propaganda

Cite as: APA style: Kuči, G. (2024). Russia’s hybrid warfare in the western Balkans: geopolitical strategies and proxy actors. Octopus Journal: Hybrid Warfare& Strategic Conflicts, 3. https://doi.org/10.69921/29031991

(CC BY-NC 4.0) This article is licensed to you under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. When you copy and redistribute this paper in full or in part, you need to provide proper attribution to it to ensure that others can later locate this work (and to ensure that others do not accuse you of plagiarism).

Introduction

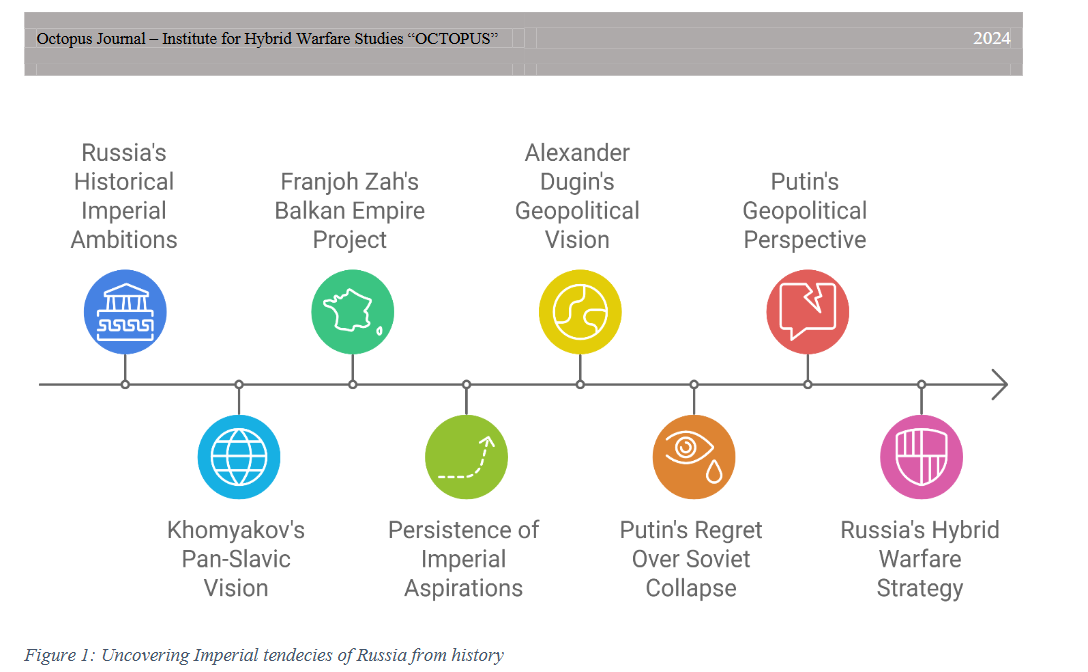

The Balkans as a whole, and the Western Balkans in particular, have consistently been targets of Russian expansionist ambitions. These intentions extend beyond mere territorial aspirations; they are deeply intertwined with historical, cultural, and geopolitical factors. During the era of Tsarist Russia, the philosopher Aleksey Stepanovich Khomyakov, a prominent Slavophile, published a controversial article titled “On the Old and the New” in 1839. This work articulated a vision for a Pan-Slavic empire that sought to unify Slavic peoples under Russian leadership, reflecting an enduring ambition that would shape Russia’s foreign policy for generations (Rakitin, 2013).

Khomyakov’s philosophy laid the groundwork for subsequent Russian efforts to forge an empire stretching from the Pacific Ocean in the East to the Adriatic Sea in the West. This vision encompassed not only the eastern borders of Austria and Prussia but also extended to Norway (Rakitin, 2013). Franjoh Zah later proposed a project aimed at consolidating the Slavs of the Balkans into an empire, which was envisioned to unfold in two phases: first through “liberation wars” and subsequently through ethnic cleansing of territories deemed as “Slavic living space” (Batakovic, 2014). The principles outlined in works such as “Nacertanije” (1844) by Ilija Garasanin and the Bulgarian Otoqefanos program further illustrate this imperial ambition (Batakovic, 2014).

Despite significant political changes over the years, including the fall of the Tsarist Empire and the rise and fall of Bolshevism, Russia’s imperial aspirations have persisted. Alexander Dugin’s 1997 book “Foundations of Geopolitics: The Geopolitical Future of Russia” articulates a strategic vision that seeks to reassert Russian influence globally, particularly in Eurasia. Dugin posits that the geopolitical landscape is fundamentally divided between “Tellurocracies” (land powers) and “Thalassocracies” (sea powers), positioning Russia as a primary land power that must counteract Atlanticist dominance through engaging in strategic territorial expansions, such as the annexation of Ukraine and the establishment of a “Moscow-Tokyo Axis” to enhance influence in the Far East. He emphasizes the necessity of using Russia’s natural resources to exert pressure on other nations, advocating for a geopolitical strategy that includes subversion and destabilization of Western interests to achieve a multipolar world order where Russia plays a central role.

President of Russia in 2004, in an address following the Beslan school hostage crisis, he expressed his regret over the collapse of the Soviet Union describing it as a time when “we stopped paying the required attention to defense and security issues and we allowed corruption to undermine our judicial and law enforcement system” (Kremlin, 2004).

Putin further elaborated on his views regarding the Soviet collapse in later speeches and interviews. For instance, in his 2005 annual address to the Federal Assembly, he famously described the dissolution of the USSR as “the biggest geopolitical catastrophe of the century” (Dickinson, 2022). He qualified this statement by adding that “for the Russian people, it became a real drama. Tens of millions of our citizens and countrymen found themselves outside Russian territory” (Dickinson, 2022).

In a 2021 essay titled “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians”, Putin expanded on his perspective, describing the fall of the USSR as “the disintegration of historical Russia under the name of the Soviet Union” (Dickinson, 2022). He lamented that “what had been built up over 1,000 years was largely lost” (Dickinson, 2022).

Putin made it clear that he views the collapse of the Soviet Union as a geopolitical setback that undermined Russia’s security and influence on the global stage. His writings and speeches disclosed desire to reassert Russia’s power and reintegrate former Soviet territories, particularly Ukraine, into Moscow’s sphere of influence.

Russia’s imperial aspirations are presently being advanced predominantly through unconventional strategies, which are collectively referred to as “hybrid warfare”. This phenomenon is increasingly evident as a form of global confrontation.

Nevertheless, this paper will explicitly focus on Russia’s hybrid warfare tactics employed in the Western Balkans. The region’s unique vulnerabilities—marked by ethnic divisions, weak political institutions, and economic challenges—create fertile ground for hybrid tactics such as disinformation campaigns and cyberattacks.

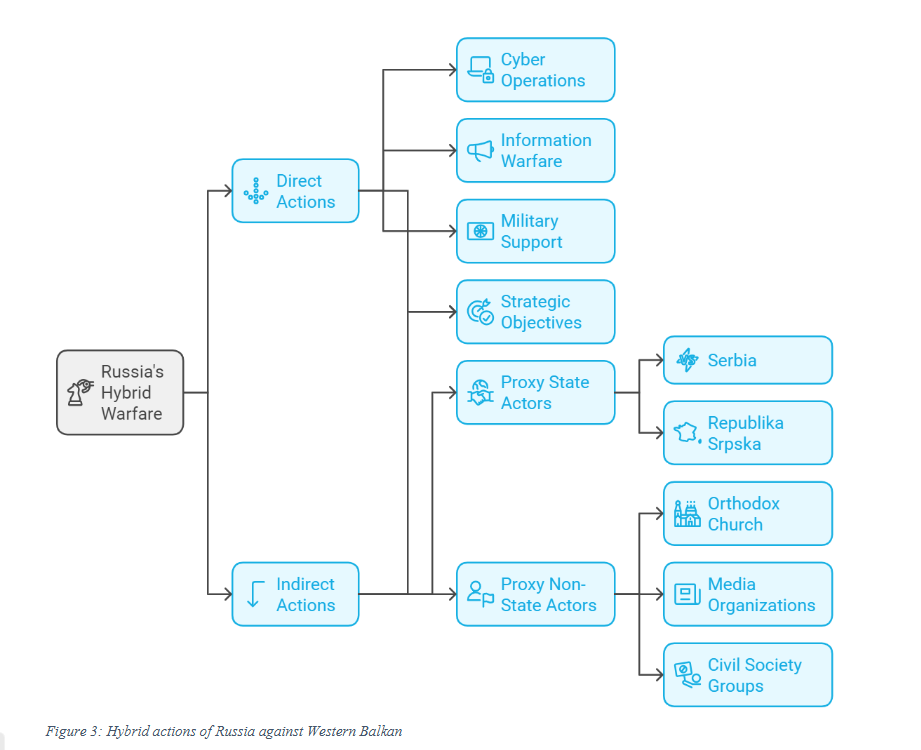

Russia’s hybrid warfare strategy employs both direct actions and indirect methods through proxy actors. Directly, Russia utilizes media outlets like Sputnik and Rybar to disseminate narratives that align with its interests. Indirectly, it leverages state actors such as Serbia and Respublika Srpska alongside non-state entities like the Orthodox Church and pro-Russian organizations to exert influence while minimizing direct confrontation with Western powers.

This paper will analyze how Russia’s hybrid warfare methods are employed against Western Balkan countries and their implications for regional stability.

Research questions

1.What hybrid warfare methods does Russia employ against Western Balkan countries, and how do these methods exploit the region’s vulnerabilities?

2.How does Russia use proxy actors (both state and non-state) to influence political and social dynamics in the Western Balkans?

3.What role do elections play in Russia’s geopolitical strategy in the region, and how does electoral manipulation contribute to its broader hybrid warfare objectives?

The dependent variable focuses on methods of hybrid warfare employed by Russia against Western Balkans countries.

Methodology

This study adopts a multidisciplinary qualitative research framework to analyze the hybrid warfare strategies employed by Russia in the Western Balkans. The investigation integrates insights from various disciplines, including political science, international relations, military studies, and media analysis, to offer a thorough understanding of Russia’s impact on the region. By employing a blend of historical-comparative analysis and case study methods, the research delineates the progression of Russian geopolitical tactics, with a particular emphasis on case studies such as Montenegro and North Macedonia. These specific instances facilitate a detailed exploration of both overt and covert hybrid warfare techniques, encompassing media manipulation, electoral interference, and the deployment of proxy forces.

Furthermore, the study utilizes content analysis to examine the influence of pro-Russian media platforms like Sputnik and Russia Today, investigating the mechanisms through which disinformation and propaganda are leveraged to undermine regional stability. This qualitative methodology, bolstered by an examination of historical records and contemporary geopolitical theories, fosters a sophisticated understanding of the political and social dynamics that Russia seeks to exploit. Through this multidisciplinary perspective, the research illustrates that hybrid warfare transcends traditional military approaches, incorporating elements of cultural, religious, and political manipulation, thereby highlighting the intricate nature of contemporary geopolitical conflicts.

Theoretical background

Hybrid warfare is a multifaceted concept that involves the simultaneous application of conventional, unconventional, cyber, and informational methods to achieve strategic objectives (NATO, 2020). The term “hybrid warfare” gained significant prominence after the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah conflict, which demonstrated the effective combination of guerrilla tactics with modern technology (Mecklin, 2017). However, the roots of hybrid warfare can be traced to ancient military strategies. Sun Tzu’s “The Art of War” emphasizes the use of deception, indirect methods, and adaptability, all of which align with modern hybrid warfare concepts (Jacobs & Kitzen, 2019).

Hybrid warfare involves the blending of traditional military power with unconventional tactics, including cyberattacks, disinformation, economic coercion, and political manipulation (Mecklin, 2017; Lanoszka, 2016). This combination allows state actors to achieve strategic goals without engaging in full-scale conventional conflict, making it a particularly attractive tool for countries like Russia, which have utilized these methods extensively in recent years.

Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and its involvement in Eastern Ukraine serve as prime examples of hybrid warfare. In these cases, Russia employed a mix of cyber operations, information warfare, and support for irregular forces to achieve its objectives without resorting to overt military aggression (Muradov, 2022; Lanoszka, 2016). This model of hybrid warfare has been adapted and applied to other regions, including the Western Balkans, where Russia seeks to undermine regional stability and prevent integration with Western institutions like NATO and the European Union (Beraia, 2021).

Hybrid warfare is not merely a military strategy; it is also deeply rooted in the political and economic vulnerabilities of the target regions. In the Western Balkans, long-standing ethnic divisions, weak political institutions, and economic underdevelopment create fertile ground for hybrid tactics, including cyberattacks and disinformation campaigns (Dolan, 2022; Bihari, 2019). Russia has exploited these vulnerabilities, leveraging its historical, cultural, and religious ties to the region. Through carefully crafted media narratives and diplomatic efforts, Russia has been able to project influence and cultivate pro-Russian sentiment, particularly in Serbia and Republika Srpska (Trifunović & Obradovic, 2020; Krasniqi et al., 2023; Lanoszka, 2016)

One of the key components of Russia’s hybrid warfare strategy in the Western Balkans is the use of proxy actors. These include both state actors, such as Serbia and Republika Srpska, and non-state actors, such as the Orthodox Church, media organizations, and civil society groups aligned with Russian interests (Lanoszka, 2016). Proxy actors allow Russia to exert influence indirectly, minimizing the risk of direct confrontation with Western powers while still achieving its strategic objectives (Krasniqi et al., 2023).

In addition to proxy actors, Russia has employed “soft power” as part of its hybrid strategy. Soft power tactics involve the promotion of Russian culture, language, and ideology through cultural and educational programs (Trifunović & Obradovic, 2020). These initiatives help to build long-term influence by shaping the perceptions of local populations, particularly in countries with historical ties to Russia. Such methods are crucial for implementing Russia’s broader strategic goals in the region, including weakening the influence of NATO and the EU.

Finally, it is essential to recognize that Russia’s hybrid warfare tactics in the Western Balkans bear significant similarities to those employed in other regions, particularly in Ukraine and Georgia. In all cases, Russia has sought to limit the foreign policy autonomy of neighboring states by destabilizing their internal political landscapes and undermining their alliances with Western institutions (Lanoszka, 2016; Muradov, 2022). By using a combination of disinformation, cyberattacks, and political manipulation, Russia aims to weaken the institutional integrity of these regions, thereby preventing them from integrating into NATO and the EU (Beccaro, 2021).

The Western Balkans, with its geopolitical importance and historical ties to Russia, remain a focal point for Moscow’s hybrid warfare efforts. Accelerating the integration of Western Balkan countries into NATO and the EU is seen as a critical step to counter Russian influence and prevent future conflicts (Krasniqi et al., 2023).

So, we can conclude that Russia’s hybrid warfare against the Western Balkans has developed and continues to operate in two main forms:

1.In a direct form by Russia itself.

2.In an indirect form through its “Proxy” actors, which are divided into two subcategories:

2.1. Proxy state actors –including states and federal entities.

2.2. Proxy non-state actors –including the Orthodox Church, associations, organizations, various interest groups, political parties, media, etc.

Models of Russia’s hybrid warfare against Western Balkan

Direct form

Russia, in its efforts to extend its influence through hybrid warfare in the Western Balkans, has employed tools such as media outlets directly managed by Russia, for example, Sputnik and Rybar. Additionally, Russia has established associations directly managed by Moscow and has set up so-called humanitarian military centres. Furthermore, recruitment centres have been created, such as the Wagner Group’s facility in Serbia.

Media operating in the Western Balkans directly under the auspices of Russia include:

Sputnik–Established in Serbia in 2016, Sputnik was founded in 2014 by a decree from Russian President Vladimir Putin, who was first in Russia.

Russia Today (RT)–While it does not have an official office in the Western Balkans, RT publishes news in Serbian and other languages. It functions as a state-sponsored media outlet from Russia and its news is extensively disseminated by media in the Western Balkans, particularly those aligned with Russian interests.

RYBAR –This channel publishes military analyses related to Russia’s conflict with Ukraine, aiming to influence media and public opinion in line with Russian interests. RYBAR has also addressed issues concerning the Western Balkans, particularly Serbia and Kosovo. In April of this year, RYBAR announced the establishment of a media school in the Western Balkans, though it did not specify the location, only noting that teams from Serbia and Republika Srpska were involved in educational activities related to the Telegram social network (RYBAR, 2024).

Russia has directly operated in the Western Balkans, particularly in Serbia, through the Wagner Group, which has also been reported to act violently in Kosovo.

-In late 2022, Wagner officially opened a “cultural center” in Serbia with the aim of engaging in informational confrontation with Russian liberals working against Moscow in Serbia. The center, called ORLY, appointed Alexander Lisov as its leader, an individual who had been banned from entering Kosovo. During protests in Leposavic last year (2023), several individuals were seen wearing shirts displaying the symbols of the Russian Wagner Group. Additionally, efforts have been made to recruit Serbs. Although President Vucic has criticized and denied any connection with the group, he has not opposed the opening of the center.

-Russian Serbian Humanitarian Centre -located in Nis, Serbia, is an intergovernmental nonprofit organization established on April 25, 2012. Its founding was based on a cooperation agreement between the Russian Federation and Serbia, signed by the respective ministers of emergency situations and internal affairs at the time (RSHC, n.d.).The centrehas faced scrutiny and criticism, particularly from Western nations, which have expressed concerns that it could serve as a cover for Russian intelligence activities. In 2017, Russian officials sought diplomatic status for the centre, but this was met with opposition from the United States and other Western countries. They argued that granting such status could lead to increased Russian military presence in Serbia and undermine the country’s sovereignty.

Recent reports indicate that there are discussions within the Serbian government about potentially changing the status of the RSHC, possibly as a response to pressures to align more closely with European Union foreign policy and to impose sanctions on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine. This has sparked debates about the centre’s future and its role in Serbian-Russian relations(FoNet, 2022) (Djurdjic, 2017). This center is a direct influence as it is an interstate agreement.

–Military and security ties -Serbia has maintained strong military cooperation with Russia, which includes the supply of military hardware and joint exercises. For instance, Serbia has received various military equipment from Russia, such as MiG-29 jets and Pantsir-S1 air defence systems, as part of a military-technical assistance agreement signed in 2016(Zweers et al., 2023) (Ejdus, 2024). This military relationship extends to intelligence sharing, particularly in areas like counterterrorism and counterintelligence.

–Direct intelligence exchanges: Serbian officials, including the Director of the Security Information Agency, have reportedly received intelligence from Russian counterparts. For example, during a recent visit to Moscow, Serbian Deputy Prime Minister Aleksandar Vulin expressed gratitude to Russian security structures for providing warnings about potential unrest in Serbia, which the government described as attempts at a coup (RFE/RL’s Balkan Service, 2024; Ejdus, 2024). This indicates a direct line of communication and cooperation between the intelligence agencies of both countries.

–Russia’s intelligence cooperation with Serbia also aims to bolster the Serbian government’s stability in the face of domestic protests and Western pressure. The Kremlin has been known to support Serbian authorities in portraying opposition movements as foreign-backed attempts to destabilize the government, thus reinforcing the narrative that Serbia must maintain close ties with Russia for its national security (Stanicek & Caprile, 2023).

Indirect form

The indirect form of hybrid warfare utilized by Russia in the Western Balkans is characterized by the strategic use of proxy actors. This approach allows Russia to exert influence while minimizing direct confrontation with Western powers. Proxy actors can be categorized into two main groups: proxy state actors and proxy non-state actors. This chapter will delve into these categories, examining their roles, functions, and implications for regional stability.

Proxy state actors

Proxy state actors are pivotal to Russia’s strategy in the Western Balkans, allowing Moscow to exert influence without direct engagement. The cooperation between Russia and states like Serbia and the autonomous entity of Republika Srpska within Bosnia and Herzegovina exemplifies this tactic. These actors enable Russia to project its power and destabilize the region by leveraging geopolitical, ideologicaland civilizational alignments.

Serbia as a proxy

Serbia, with its historical and cultural ties to Russia, is a key state actor in Russia’s hybrid warfare strategy. The alignment between Moscow and Belgrade is built upon shared Orthodox Christian values, Slavic identity, and geopolitical interests. Serbia’s military and political ties with Russia, such as the procurement of Russian military equipment like the MiG-29 jets and Pantsir-S1 air defense systems, further cement this relationship (Mitrović, 2017). Additionally, joint military exercises such as “Slavic Brotherhood “underscore this cooperation (Barros, 2021).

Russia also exerts its influence on Serbia through diplomatic channels and intelligence sharing. For instance, in 2021and 2024, Russian intelligence warned Serbia of potential unrest, reinforcing the narrative of foreign-backed destabilization efforts and encouraging Serbia to maintain close ties with Russia for security reasons (Vulin, 2021; Gotev, 2024). This strategic use of Serbia as a proxy allows Russia to challenge Western institutions like NATO and the European Union without direct confrontation.Serbia as an EU candidate signed also an agreement with Russia to coordinate foreign policy(AP, 2022).

Despite the West’s policy of appeasement towards Serbia, recently Serbia has once again aligned its approach with Russia against Kosovo, invoking UN Resolution 1244. This has been confirmed by Zakharov’s calls on Vucic to return Serbian military forces to Kosovo (Musliu & Kuçi, 2024).

Republika Srpska as a proxy entity

Within Bosnia and Herzegovina, Republika Srpska functions as another critical state proxy for Russia. Moscow’s support for the separatist ambitions of Republika Srpska strengthens its influence in the region. The political leadership of Republika Srpska, notably under Milorad Dodik, has consistently aligned itself with Russian interests, advocating for closer ties with Moscow and opposing Bosnia’s integration into NATO (Bieber, 2018).

Dodik’s rhetoric often echoes Kremlin narratives, particularly regarding Western interference and the promotion of pro-Russian policies. This relationship not only serves to undermine Bosnia’s sovereignty but also destabilizes the broader region by fostering ethnic tensions and obstructing the integration of the Western Balkans into Euro-Atlantic structures (Krasniqi & Obradovic, 2023).

Proxy non-state actors

While we previously mentioned some direct interventions by Russia through non-state actors, it is essential to emphasize the existence of a distinct category of non-state actors that function indirectly as proxies. This group includes political parties, organizations, churches, media outlets, and other interest groups that have been established by pro-Russian individuals, are funded by Russia, and actively advance its strategic goals and influence. Although these actors are legally and officially independent, they frequently operate in alignment with Russian interests, effectively serving as tools of its foreign policy under the guise of autonomy.

Political parties and organizations

Pro-Russian political parties and organizations in the Western Balkans act as conduits for Russian influence. These groups, often nationalist in orientation, share Moscow’s geopolitical goals of resisting Western influence and opposing NATO expansion. For instance, in Montenegro, the Democratic Front (DF) has consistently advocated for closer ties with Russia and has opposed Montenegro’s NATO membership (Popović, 2017). The DF’s leadership has openly supported Russian policies and has been accused of accepting financial backing from Moscow (Bami, 2023). Similar dynamics exist in Serbia, where pro-Russian organizations such as the Serbian Russian Friendship Association promote Russian culture, language, and political values. These organizations are instrumental in fostering a favourable view of Russia and shaping public opinion against Western alliances.

SNS party that is now in power in Serbia has some figures that are directly connected with Russia and President of Serbia, Alexander Vucic use them to protect connections with Russia and BRICS and itself to say in a multi-vector approach.

In addition to these methods, Russia also employs “soft power “as a potent tool in its hybrid warfare strategy. This includes the promotion of Russian culture, language, and ideology through cultural and educational programs, which are designed to influence the mindset of local populations and foster sympathy for Russia in the Western Balkans. This subtle form of influence is a critical component in the practical execution of Russia’s hybrid warfare strategy, as it shapes public opinion and strengthens its foothold in the region through non-state actors.

The Orthodox Church

The Serbian Orthodox Church (SOC) plays a crucial role in promoting Russian influence in the Western Balkans. With its deep religious and historical ties to the Russian Orthodox Church, the SOC has often aligned itself with Moscow’s geopolitical interests. The Church’s opposition to Western liberal values and its support for pro-Russian political movements make it a powerful non-state actor in Russia’s hybrid warfare strategy (Hudson, 2019).

Through cultural and religious narratives, the SOC fosters a sense of Slavic unity and Orthodox solidarity, which Russia exploits to bolster its influence in Serbia and Republika Srpska (Bieber, 2018). This religious dimension provides Moscow with a unique avenue to cultivate loyalty and support within the population, particularly in times of political tension.

Media outlets

Pro-Russian media outlets in the Western Balkans are essential tools in Russia’s hybrid warfare strategy. Channels such as Sputnik and Russia Today (RT) disseminate narratives that align with Russian foreign policy objectives, often focusing on disinformation campaigns aimed at discrediting Western institutions and promoting Russian geopolitical interests (Dolan, 2022). These media outlets are instrumental in shaping public opinion and fostering skepticism towards NATO and the European Union. In Serbia, for example, Sputnik has established a significant presence, providing a platform for pro-Russian voices and reinforcing anti-Western sentiment (Judita Krasniqi et al., 2023). By controlling the flow of information, Russia can maintain a favorable public image while undermining the credibility of Western alliances.

Based on the Bureau for Social Research (BIRODI) they inform that at least 41 media are influenced by the Vucic regime and consequently by Russia (Geopost, 2024). Surveys indicate a strong pro-Russian sentiment among Serbian citizens, with many attributing blame for conflicts like the war in Ukraine to Western powers rather than Russia. For instance, a survey found that 66% of Serbians believe the West is responsible for the war in Ukraine, while only 21% blame Russia(Zweers et al., 2023).

Case study1: Hybrid warfare in Montenegro

Montenegro, a small territory with a coastline of 293.5 kilometers and a maritime space of 2,540 square kilometers, is far more than a geographic fragment. It represents a geostrategic point of significant interest for major global powers. Following the dissolution of empires and the conclusion of World War I, Serbia took advantage of the political vacuum left by King Nikola’s departure to annex Montenegro. In December 1918, Serbia swiftly imposed its influence, orchestrating a referendum and convening a Montenegrin assembly. This assembly was used to rubber-stamp Montenegro’s union with Serbia before being dissolved shortly thereafter (Pavlović, 2008; Littlefield, 1922). This act of forced incorporation marked the beginning of a long-standing Serbian influence over Montenegro, which persisted throughout the 20th century, with Montenegro only regaining full sovereignty at the dawn of the 21st century after the dissolution of Yugoslavia.

By the late 1990s, under the leadership of Milo Đukanović, Montenegro began to chart a path towards Western integration, gradually distancing itself from Serbia and Yugoslav leadership. Djukanovic and Svetozar Marovic, following a visit to the Pentagon in 1995, offered the Port of Bar for logistical support to international peacekeepers in Bosnia and Herzegovina, positioning Montenegro as an independent actor on the international stage (Morrison, 2018). This move positioned Djukanovicas a key figure in Montenegro’s journey towards NATO and European Union membership, a process fraught with challenges, including an assassination attempt on his life. Djukanovicnegotiated to limit NATO airstrikes on Montenegro during the 1999 NATO bombings of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia(Morrison, 2018), maintaining a diplomatic stance that strengthened Montenegro’s ties with the West.

The refusal of Montenegro to allow the installation of a Russian military base at the Port of Bar in 2013 and 2015 further solidified the country’s Euro-Atlantic orientation, deepening tensions with both Russia and Serbia. As Murati (2014) argues, these actions were seen as a geopolitical challenge to NATO, altering the balance of power in the Adriatic. Efforts to thwart Montenegro’s NATO accession culminated in a 2016 assassination plot against Djukanovic, which involved Serbian and Russian operatives.20 individuals were arrested in connection with the plot, including former Serbian gendarmerie leaders and two Russian nationals (Tomović, 2018). Despite these challenges, Montenegro successfully joined NATO in 2017, solidifying its commitment to Western structures.

The 2020 parliamentary elections marked a turning point in Montenegro’s political landscape, ending the long dominance of the Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS). The victory of the “For the Future of Montenegro “coalition, led by Zdravko Krivokapic, brought a dramatic shift, with a new government supported by right-and left-wing political forces. However, this government quickly faced instability, culminating in the fall of Dritan Abazović, Montenegro’s first Albanian prime minister. Abazović’s controversial agreement with the Serbian Orthodox Church (SOC) granted extraterritorial rights to the church and other benefits, fueling political tensions and leading to his downfall. This agreement “granted extraterritorial rights to the Serbian Orthodox Church and a host of other privileges”, sparking widespread opposition and further political destabilization in Montenegro (Kuka, 2022).

Following Abazovic’s departure, the 2023 elections failed to produce a clear resolution to Montenegro’s political polarization, resulting in a coalition government of 11 parties, with Milojko Spajić as prime minister. However, concerns were raised about the pro-Serbian and pro-Russian influence within the new government, particularly due to Spajic’s ties to political actors in Republika Srpska and Serbia. Igor Dodik, son of Republika Srpska President Milorad Dodik, played a key role in building Spajic’s party, highlighting the strong influence of pro-Russian and pro-Serbian forces in Montenegro’s new government (Vijesti, 2024). These developments signal a worsening of Montenegro’s Western orientation, with a potential shift towards Serbia and Russia, raising new challenges for the country’s political stability.

The latest census in Montenegro has unveiled external interventions and attempts to manipulate the national identity structure, particularly through Serbian influence. Political campaigns and the involvement of the Serbian Orthodox Church have promoted a Serbian identity for the Montenegrin population, with slogans such as “You are not Montenegrin if you are not Serbian” (Vijesti, 2023b). Patriarch Porfirije, in a speech in Podgorica, urged Orthodox believers to identify as Serbs to preserve their national and religious identity (Vijesti, 2024). These actions have been accused of being part of an “ethnic engineering “effort, as local politicians like Daniel Zivkovic argue, raising concerns over the integrity of the census process (Obradović, 2023).

Serbia’s interference in Montenegro’s census is viewed as part of a broader geopolitical strategy aimed at altering ethnic balances and undermining Montenegro’s independence. Former President Djukanovic has claimed that Serbia aims to dismantle Montenegrin national identity to reinforce the narrative of Montenegro as part of a Greater Serbia (Vijesti, 2023c). Reports of manipulation during the census process, including the use of erasable pens and falsified voter lists in Podgorica, have heightened suspicions of a rigged outcome designed to reflect Serbian and Russian geopolitical interests (Salaj, 2023).

Historically, census data reveal a significant increase in Montenegro’s Serbian population, particularly following the dissolution of Yugoslavia. The percentage of Serbs in Montenegro rose from 1.8% in 1948 to 28.7% in 2011(Statistical Office of Montenegro -MONSTAT, n.d.). This demographic shift is closely linked to Serbia’s geopolitical strategies, providing both Serbia and its ally Russia with a tool to destabilize the region. The limited release of census results and the lack of transparency from Monstat have further fueled suspicions of census manipulation, casting doubt on the integrity of Montenegro’s national identity and independence.

The hybrid warfare employed by Russia, in cooperation with its proxy Serbia, against Montenegro has been remarkably sophisticated, utilizing democratic mechanisms to further its aims. Through electoral procedures, cultural and religious influence, political manipulation, and ethnic engineering, Russia has succeeded in positioning pro-Russian and pro-Serbian politicians at the helm of Montenegro’s institutions. This strategy introduces a new element that we define in the paper “Geopolitical Risks and Reconfigurations: Serbia and the Challenge to Montenegro’s Stability” as “electoral geopolitics”. This term encapsulates how elections can be weaponized as a geopolitical tool to destabilize nations and shift their strategic alignment.

For more information on the hybrid warfare strategies of Russia and Serbia in Montenegro, please refer to the cited work (Kuçi, 2024).

Case Study 2: North Macedonia

In the last decade, Russia has consistently sought to destabilize North Macedonia and block its integration into NATO and the European Union. Leaked documents from the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and its partners show that Russian diplomats and agents recruited Macedonian officials and financed media outlets, including those with anti-Albanian rhetoric, in an attempt to create a state politically dependent on Russia (Belford et al., 2017). Furthermore, Russia has funded Pan-Slavic activities through the Serbian Church and built new structures, such as churches and crosses in the Russian style, to deepen its cultural influence. The policies of the VMRO-DPMNE under Nikola Gruevski supported this pro-Russian and pro-Serbian orientation, contributing to the refusal of sanctions against Russia after the annexation of Crimea in 2014 (Mujanović, 2018).

Following Gruevski’s fall, Russian influence was severely diminished, but Moscow continued its efforts to thwart the Prespa Agreement, which changed the country’s name and paved the way for Euro-Atlantic integration. According to intelligence documents, agents of Serbia’s BIA and pro-Russian Macedonian deputies cooperated to destabilize the country and promote an anti-NATO agenda (Noack, 2021). Despite these efforts, Zoran Zaev’s victory in the subsequent elections marked a significant shift, temporarily curbing Russian and Serbian influence in the region and clearing the way for North Macedonia’s pro-Western orientation.

Russia’s engagement in obstructing North Macedonia’s progress toward NATO and the EU has been marked by continuous efforts to interfere in its relations with neighboring states, disrupt diplomatic processes, and influence public opinion. By leveraging historical and ethnic tensions in the region, Russia has employed various tactics, such as financial backing of anti-NATO actors and supporting the disruption of the name agreement with Greece. Russian diplomats were reportedly involved in corrupting Orthodox religious figures and senior officials to prevent improving relations between the two countries (Deutsche Welle, 2018; Benakis, 2018), which led to the expulsion of Russian diplomats from Greece (Nedos, 2018). In 2018, the Russian ambassador to North Macedonia warned that joining NATO would turn Skopje into a target for Russian attacks if Moscow felt threatened (Drapak, 2023). These actions align with Russia’s broader Balkan strategy, where support for pro-Russian groups and the use of Serbia as a proxy have been part of its policy to destabilize the region (McBride, 2023).

Russian intervention also extends to efforts to deepen divisions between North Macedonia and Bulgaria, aiming to undermine progress towards Euro-Atlantic integration. As Daniel Suter points out, Russia has, for decades, exerted diplomatic, propaganda, and intelligence pressure to portray North Macedonia as a victim of its Neighbours, such as Bulgaria and Greece, accusing the Skopje government of capitulating to Bulgarian demands (Sunter, 2020). Despite a compromise mediated by France, Macedonian public opinion remains skeptical, with a majority opposing the current EU integration conditions (Анкета На ИПИС, 2022). As tensions between North Macedonia and Bulgaria persist, Russian influence has fueled the rise of pro-Russian and pro-Serbian political parties, such as VMRO-DPMNE and Levica, which oppose NATO and EU membership, particularly based on agreements influenced by Bulgaria.

The war in Ukraine has renewed interest in North Macedonia, especially in the context of the expulsion of Russian diplomats from the country. Since the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, North Macedonia has declared several Russian diplomats “person anon grata”, as part of an effort to limit Russian influence in the Balkans. This stance aligns with Western efforts to counter Russian and Serbian ambitions in the region, which are based on the ideological projects “Russky Mir” and “Serpski Svet”. According to analyst Vuksanovic (2018), Russia seeks to undermine Western unipolarity in the Balkans, using Serbia as a “proxy “to advance its multipolar world order.

The Russo-Serbian influence is reflected not only in the diplomatic sphere but also in the political discourse in the Balkans. In North Macedonia, this tandem’s influence has manifested through propaganda promoting fears of the creation of a “Greater Albania “in upcoming parliamentary elections. This strategy is part of a broader effort to halt the advancement of Balkan countries toward NATO and the EU, aiming to create a concert of powers based on a multipolar order (Secrieru, 2018). In this context, Serbia and Russia mutually benefit, with Serbia acting as an intermediary to advance shared ideological and geopolitical agendas.

The dissatisfaction of North Macedonia’s citizens with the government and the perception of its limited international influence have created space for external actors, including Russia, China, and Turkey, to exert influence. Frustration with the European Union has created a vacuum in which Russia and other actors capitalize on internal grievances for geopolitical purposes (Rechica, 2023). The “Skopje 2014” project of the Gruevski government is an example that demonstrates large-scale construction efforts, but also deep-seated corruption, creating a general atmosphere of economic and social stagnation (Dimitrievska, 2024).

Russian and Serbian interference in the region was also seen in the context of Montenegro’s 2020 elections, which ousted a pro-Western government, serving as a warning for potential future impacts in North Macedonia. Corruption and economic stagnation have fueled citizen dissatisfaction with pro-Western parties, creating space for the rise of anti-Western political forces (Brey, 2023). This dissatisfaction with the government and the EU, along with the erosion of “uzurpocracy”, has fueled anti-Western sentiments, making North Macedonia and the region vulnerable to Russian Serbian interference.

The 2016 elections in North Macedonia marked a significant shift in the country’s political orientation, moving from a pro-Serbian and pro-Russian regime to a pro-Western approach. Ljubco Georgievski’s campaign, with the slogan “Stop the Serbian assimilation of the Macedonian nation” (Filipovic & Pejic, 2015), sparked internal tensions, dividing Macedonian politics and accelerating the fall of Gruevski’s regime and VMRO-DPMNE. The involvement of ethnic Albanians as a key factor in this transformation towards a pro-Western perspective was crucial, reinforcing North Macedonia’s new orientation towards European integration. Electoral elections that were held in May 2024, brought to power the opposition VMRO-DPMNE which immediately began to show serious pro-Russian and pro-Serbian tendencies starting from the non-recognition of the name.

Electoral processes have transitioned from internal issues to a significant geopolitical factor, particularly in the context of countries with fragile democracies like North Macedonia and Montenegro. These processes have become battlegrounds for hybrid warfare, employed by autocratic regimes like Russia and Serbia, which seek to manipulate elections to influence alliances and strategic orientations of other nations. The manipulation of democratic processes is a manifestation of hybrid warfare, where political, economic, and informational strategies are used to achieve strategic objectives.

For more information on the hybrid warfare strategies of Russia and Serbia in North Macedonia, please refer to the cited work (Kuçi, 2024).

Conclusions

This analysis of Russia’s hybrid warfare strategies in the Western Balkans has revealed the complex interplay of historical, cultural, and geopolitical elements that inform Moscow’s strategic maneuvers. The results highlight several key conclusions that contribute to a nuanced understanding of the nature, effects, and wider ramifications of Russia’s activities in the region.

1.Bifurcated nature of hybrid warfare

Russia’s hybrid warfare encompasses both overt and covert tactics, employing state-run media, military alliances, and proxy groups to create instability in the region. Overt actions include the use of media platforms such as Sputnik and Russia Today, alongside military cooperation with Serbia and Republika Srpska. Covertly, Russia influences political landscapes through non-state entities like the Serbian Orthodox Church and pro-Russian factions, enabling Moscow to sustain plausible deniability while pursuing its geopolitical aims. This bifurcation renders hybrid warfare an effective mechanism for shaping the political and social dynamics of the Western Balkans without engaging in direct conflict.

2.Exploitation of regional vulnerabilities

Russia’s approach leverages enduring weaknesses within the Western Balkans, such as ethnic discord, unstable political frameworks, and economic fragility. By exacerbating local discontent, Russia aims to obstruct the region’s progression towards NATO and the European Union. This exploitation presents a dual challenge: it erodes regional governance mechanisms and fosters broader instability, rendering the area vulnerable to external manipulation, which further complicates international initiatives aimed at stabilizing Southeast Europe.

3.Impact on electoral processes and democratic integrity

A critical element of Russia’s hybrid warfare strategy is the interference in electoral processes within nations like Montenegro, North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia, but exist cases also in Kosovo. By bolstering pro-Russian groups and undermining pro-Western candidates, Moscow actively alters the political dynamics to its advantage. This tactic not only diminishes democratic integrity but also sustains a cycle of political instability that obstructs the region’s efforts to establish democratic norms and institutions. Russia’s manipulation of electoral processes illustrates the perilous intersection of hybrid warfare and electoral geopolitics, where democratic mechanisms are exploited to further geopolitical ambitions.

4.Broader geopolitical implications

The hybrid warfare employed by Russia in the Western Balkans signifies a larger geopolitical strategy aimed at altering global power relations. This approach extends beyond the Balkans, reflecting Moscow’s overarching goal of fostering a multipolar world order that contests Western hegemony. Through a blend of media manipulation, cultural outreach, and clandestine operations, Russia seeks to erode the institutional foundations of NATO and the European Union, thereby establishing spheres of influence that may result in a reconfiguration of geopolitical alliances throughout Eurasia.

5.Need for enhanced Western engagement.

The paper highlights the pressing necessity for a unified Western response. Russia’s hybrid strategies, though often subtle, pose a considerable risk to regional sovereignty and the process of Euro-Atlantic integration. A proactive and multifaceted strategy—incorporating improved intelligence sharing, robust cybersecurity initiatives, and support for independent media—is vital for counteracting Russian influence. Furthermore, strengthening resilience within democratic institutions and civil society is crucial to countering the impacts of disinformation campaigns and external meddling, thereby safeguarding the Western Balkans from further destabilization.

6.New paradigm of conflict: Hybrid Warfare and regional sovereignty

The hybrid warfare strategies utilized by Russia in the Western Balkans represent a novel paradigm of conflict, wherein unconventional tactics such as cyberattacks, media manipulation, and proxy alliances play a pivotal role in achieving strategic objectives. These operations take advantage of the region’s institutional vulnerabilities and lingering ethnic tensions, complicating efforts to stabilize and integrate the Western Balkans into the global security framework. Addressing these complex threats will require more than mere military deterrence; it will demand a holistic strategy that encompasses diplomatic, economic, and informational dimensions.

7.Dynamic characteristics of hybrid warfare

The paper indicates that Russia’s approach to hybrid warfare in the Western Balkans is characterized by its dynamic nature, adapting to both local and international changes. Russia employs a range of strategies, including soft power, intelligence collaboration, and military partnerships with both state and non-state entities to sustain its influence in the region. In response to this shifting threat landscape, countries in the Western Balkans must enhance their institutional resilience, improve cybersecurity measures, and cultivate stronger connections with Euro-Atlantic organizations to mitigate their susceptibility to external interference. In conclusion, the hybrid warfare strategies employed by Russia in the Western Balkans exemplify a complex and flexible approach designed to undermine regional stability and obstruct integration into Western frameworks.

The geopolitical consequences of these actions reach beyond the immediate area, affecting global security considerations. Therefore, comprehending and addressing Russia’s hybrid warfare is crucial not only for the stability of the Western Balkans but also for the protection of international security against the backdrop of evolving, unconventional threats.

Reference:

1.Bami, X. (2023, July 24). Russian money flowing illicitly through Western Balkans –report. Balkan Insight. Retrieved September 27, 2024, from https://balkaninsight.com/2023/07/24/russian-money-flowing-illicitly-through-western-balkans-report/

2.Barros, G. (2021). Belarus warning wpdate: Russia expands unit integration with Belarusian and Serbian militaries in June Slavic Brotherhood Exercises. In Institute for the Study of War. Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved September 27, 2024, from https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/belarus-warning-update-russia-expands-unit-integration-belarusian-and-serbian

3.Beccaro, A. (2021). Russia, Syria and hybrid warfare: A critical assessment. Comparative Strategy, 40(5), 482–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/01495933.2021.1962199

4.Belford, A., Cvetkovska, S., Sekulovska, B., & Dojčinović, S. (2017). Leaked documents show Russian, Serbian attempts to meddle in Macedonia. In OCCRP. Retrieved September 27, 2024, from https://www.occrp.org/en/spooksandspin/leaked-documents-show-russian-serbian-attempts-to-meddle-in-macedonia/

5.Benakis, T. (2018 July 12) Greece; Russia to expel diplomats in ‘Macedonia’ row. European Interest. Retrieved April 3 from https://www.europeaninterest.eu/greece-russia-expel-diplomats-macedonia-row/

6.Beraia, E. (2021). Hybrid warfare: NATO and the future of European and Asian security. In Advances in Military Textbooks (pp. 45–60). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-7118-7.ch003

7.Bieber, F. (2018). The rise of authoritarianism in the Western Balkans. Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, 20(2), 169–187.

8.Bihari, R. (2019). Orosz hibrid módszerek a Nyugat-Balkánon [Russian hybrid methods in the Western Balkans]. Hadtudományi Szemle. https://doi.org/10.32563/hsz.2019.3.1

9.Brey, T. (2023 August 30) Građani Sjeverne Makedonije više ne žele čekati Europu.[Citizens of Northern Macedonia no longer want to wait for Europe] dw.com Retrieved April 4 from https://www.dw.com/hr/gra%C4%91ani-sjeverne-makedonije-%C5%A1e-ne-%C5%BEele-%C4%8Dekati-europu/a-66660820

10.Deutsche Welle. (2018a June 13) Macedonia’s president rejects new name deal. dw.com. Retrieved April 4 from https://www.dw.com/en/macedonian-president-ivanov-says-he-wont-sign-disastrous-name-deal-with-greece/a-44212040

11.Dimitrievska, V. (2024 February 9) Voters prepare to punish North Macedonia’s ruling SDSM for broken promises [News article]. Retrieved April4 from https://www.intellinews.com/long-read-voters-prepare-to-punish-north-macedonia-s-ruling-sdsm-for-broken-promises-310569/

12.Djurdjic, M. (2017, June 19). US sees Russia’s “Humanitarian Center” in Serbiaas spy outpost. Voice of America. https://www.voanews.com/a/united-states-sees-russia-humanitarian-center-serbia-spy-outpost/3902402.html

13.Dolan, C. (2022). Disinformation and hybrid warfare: The Western Balkans as a battleground for Russian influence. European Security, 31(1), 45–67.

14.Dolan, C. (2022). Hybrid warfare in the Western Balkans: How structural vulnerability attracts maligned powers and hostile influence. SEEU Review, 17(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.2478/seeur-2022-0018

15.Drapak, M. (2023) Kremlin’s influence on Bulgaria; North Macedonia; and Montenegro in the context of Russian aggression against Ukraine. Analytical Portal. https://analytics.intsecurity.org/en/bulgaria-and-macedonia-montenegro/

16.Ejdus, F. (2024). Spinning and hedging: Serbia’s national security posture -New Lines Institute. In New Lines Institute. New Lines Institute. Retrieved September 27, 2024, from https://newlinesinstitute.org/political-systems/spinning-and-hedging-serbias-national-security-posture/

17.Filipovic, V., & Pejic, M. (2015 November25) HAJKA NA SRBE Skandalozni bilbordi mržnje po celom Skoplju; ljudi u strahu.[Hunt on Serbs Scandalous billboards of hatred throughout Skopje; people are afraid] Blic.rs Retrieved April l4 from https://www.blic.rs/vesti/politika/hajka-na-srbe-skandalozni-bilbordi-mrznje-po-celom-skoplju-ljudi-u-strahu/l0w6dbt

18.FoNet. (2022, June 20). Demostat claims Belgrade changing status of Serbian Russian humanitarian center. N1. https://n1info.rs/english/news/demostat-claims-belgrade-changing-status-of-serbian-russian-humanitarian-center/

19.Hudson, C. (2019). The role of the SerbianOrthodox Church in Russia’s Balkan strategy. East European Politics, 35(3), 211–230.

20.Jacobs, J., & Kitzen, M. (2019). Hybrid warfare: International relations perspectives on the concept and its implications for security studies. In Oxford Bibliographies in International Relations. https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780199743292-0260

21.Krasniqi, J., Hajdari, L., Maliqi, A., & Madsen, K.D.G. (2023). The mirror reflection of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in the Western Balkans: Opening new conflicts as a distraction. Access to Justice in Eastern Europe. https://doi.org/10.33327/ajee-18-6.3-a000317

22.Krasniqi, J., Obradovic, D., & Trifunović, D.(2023) Proxy war: Russia’s non-state actors in the Balkans. Hybrid Warfare Review, 15(2),90–112.

23.Kuçi, G. (2024). GEOPOLITICAL RISKS AND RECONFIGURATIONS: SERBIA AND THE CHALLENGE TO MONTENEGRO’S STABILITY. Octopus Journal: Hybrid Warfare & Strategic Conflicts,2. https://doi.org/10.69921/91pd1m30

24.Kuçi, G. (2024). HYBRID WARFARE AND THE IMPORTANCE OF ELECTIONS IN GEOPOLITICS: NORTH MACEDONIA AS A PART OF THE WEST OR RETURNING TO THE SPHERE OF RUSSIA AND SERBIA. Octopus Journal: Hybrid Warfare & Strategic Conflicts,2, 25. https://doi.org/10.69921/89mxkh20

25.Kuka, G. (2022, July 12). Çfarë përmban marrëveshja me Kishën Serbe dhe sa rrezikon Abazovic? -Euronews Albania [News article]. Euronews Albania. https://euronews.al/cfare-permban-marreveshja-me-kishen-serbe-dhe-sa-rrezikon-abazovic/

26.Lanoszka, A. (2016). Russian hybrid warfare and extended deterrence in Eastern Europe. International Affairs, 92(1), 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12509

27.Littlefield, W. (1922, April 16). Annihilation of a nation; Montenegrins’ effort to prevent annexation of their country to Serbia—Reparations Commission doesn’t know to whom to pay 13.$2,000,000 collected for Montenegro [Newspaper article]. The New York Times. Retrieved February 18, 2024, from https://www.nytimes.com/1922/04/16/archives/annihilation-of-a-nation-montenegrins-effort-to-prevent-annexation.html

28.McBride, J. (2023 November 21) Russia’s influence in the Balkans. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved April 4 from https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/russias-influence-balkans#chapter-title-0-5

29.Mecklin, J. (2017). Introduction: The evolving threat of hybrid war. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 73(5), 298–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2017.1362905

30.Mitrović, B. (2017) Serbia’s military procurement from Russia: A balancing act. Defense and Security Review, 34(1),45–60.

31.Morrison, K. (2018). Nationalism, identity and statehood in Post-Yugoslav Montenegro. In Nationalism, Identity and Statehood in Post-YugoslavMontenegro(p. 65). Bloomsbury Academic. https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/id/fe432917-bbfa-45f0-8c67-322b3058bdeb/1002488.pdf

32.Mujanović, J. (2018) Conclusions. In Hunger and Fury: The crisis of democracy in the Balkans (p .171) Oxford University Press

33.Muradov, M. (2022). The Russian hybrid warfare: The cases of Ukraine and Georgia. Defence Studies, 22(2), 168–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702436.2022.2030714

34.Murati, Sh. (2014). Mbi bazën ruse në Mal të Zi [On the Russian base in Montenegro]. In Rusa Ballkanike [Balkan Rusia] (p .335). Botimet ENEAS.

35.Musliu, A., & Kuçi, G. (2024, September 24). Scenarios after Banjska and the Russo-Serbian hybrid warfare in Kosovo. Octopus Institute. Retrieved September 29, 2024, from https://octopusinstitute.org/scenarios-after-banjska-and-the-russo-serbian-hybrid-warfare-in-kosovo/

36.Nedos, V.(2018 July 11) Greece decides to expel Russian diplomats. kathimerini.gr. Retrieved April 4 from https://www.kathimerini.com/news/greece-decides-to-expel-russian-diplomats/

37.Noack, R. (2021 December 1) Russia blames the U.S after protesters storm Macedonia’s parliament. Washington Post. Retrieved April 3 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/04/28/russia-blames-the-u-s-after-protesters-storm-macedonias-parliament/

38.Obradović, A. (2023, October 16). Zivkovic: Census aimed at ethnic engineering; BIA controls process; we’ll propose boycott if we don’t get answers by day end [News article]. CdM. https://www.cdm.me/english/zivkovic-census-aimed-at-ethnic-engineering-bia-controls-process-well-propose-boycott-if-we-dont-get-answers-by-day-end/

40.Popović, D. (2017) Pro-Russian political parties in the Balkans: The case of Montenegro. South East European Journal of Political Science, 6(2),66–82.

41.Rechica, V. (2023 June 19) The disappointment towards the West nurtures anti-democratic sentiments in North Macedonia | Politics | Res Public Retrieved April 4 from https://respublica.edu.mk/blog-en/politics/the-disappointment-towards-the-west-nurtures-anti-democratic-sentiments-in-north-macedonia/?lang=en

42.RFE/RL’s Balkan Service. (2024, August 15). EU criticizes claims of intelligence cooperation between Belgrade and Moscow. RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. https://www.rferl.org/a/serbia-russia-vulin-manturov-european-union-ukraine/33080456.html

43.RSHC.(n.d.). Russian-Serbian Humanitarian Center. Retrieved September 26, 2024, from https://www.ihc.rs/about-us/

44.RYBAR. (2024, April 24). X.com. X (Formerly Twitter). Retrieved September 26, 2024, from https://x.com/rybar_force/status/1783400095083311252

45.Salaj, A. (2023 December 16). Mali i Zi; hetime për parregullsi në regjistrimin e popullsisë [Montenegro; investigations for irregularities in population registration] [News article]. Voice of America. https://www.zëriamerikes.com/a/7400962.html

46.Secrieru, S. (2018) Russia in the Western Balkans: Tactical wins; strategic setbacks. European Union Institute for Security Studies. Retrieved April 4 from https://ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/resources/docs/EUISS_Brief%208%20Russia%20Balkans_0.pdf

47.Stanicek, B., & Caprile, A. (2023). Russia and the Western Balkans: geopolitical confrontation, economic influence and political interference | Think tank | European Parliament. In European Parliament. European Parliament. Retrieved September 27, 2024, from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2023)747096

48.Sunter, D. (2020 December 21) NATO Review -Disinformation in the Western Balkans. NATO Review. Retrieved April 4 from https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2020/12/21/disinformation-in-the-western-balkans/index.html

49.Tomovic, D. (2018, May 22). Russian, Serbian nationalists accused of plotting Montenegro coup [News article]. Balkan Insight. https://balkaninsight.com/2016/11/06/montenegro-s-prosecution-says-nationalists-from-russia-behind-coup-11-06-2016/

50.Trifunović, D., & Obradović, D. (2020) Russian influence in Serbia: A multifaceted strategy. Balkan Affairs Journal,5(1),45–67.

51.Trifunović, D., & Obradović, D. (2020). Hybrid and cyber warfare—International problems and joint solutions. National Security and the Future. https://doi.org/10.37458/nstf.21.1-2.2

52.Vijesti. (2023, October 14). Porfirije in Podgorica: We are proud to speak the Serbian language [News article]. vijesti. me Retrieved from https://en.vijesti.me/news/politics/677712/Porfirija-in-Podgorica%2C-we-are-proud-to-speak-the-Serbian-language%2C-to-be-great-members-of-the-Serbian-people-and-believers-of-the-Serbian-Orthodox-Church.

53.Vijesti. (2023, October 18). Đukanović: It is dangerous to carry out the census; the ideologues of Great Serbia want to “scratch” Montenegro [News article]. vijesti.me Retrieved from https://en.vijesti.me/news/politics/678109/Djukanovic%2C-it-is-dangerous-to-realize-the-census%2C-the-ideologues-of-Greater-Serbia-want-to-destroy-Montenegro#:~:text=%22The%20ideologues%20of%20Greater%20Serbia,the%20destruction%20of%20Montenegrin%20independence.

54.Vijesti. (2024, February 19). Dodik’s son: I helped Spajić start the party; now he has lost his identity [News article]. vijesti.me Retrieved February 20, 2024 from https://en.vijesti.me/news/politics/694804/Dodik%27s-son%2C-I_helped_Spajica_to_start_a_party%2C_and_now_he_has_lost_his_identity

55.Vuksanovic, V. (2018 July 27) Serbs are not “Little Russians.” The American Interest. Retrieved April 4 from https://www.the-american-interest.com/2018/07/26/serbs-are-not-little-russians/

56.Vulin, A. (2021) Intelligence cooperation between Russia and Serbia: A strategic partnership. Security Review Journal, 29(3), 35–47.

57.Zweers, W., Drost, N., & Henry, B.(2023). Russian sources of influence in Serbia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina | Little substance, considerable impact. In Clingedael. Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael.’ Retrieved September 27, 2024, from https://www.clingendael.org/pub/2023/little-substance-considerable-impact/russian-sources-of-influence-in-serbia-montenegro-and-bosnia-and-herzegovina/

58.Аnketa na ИPIS: Над 70% од граѓаните се против францускиот предлог. [Survey on IPIS: Over 70% of citizens oppose French proposal] (2022 July 7). Сител ТелевизијаRetrieved April 4 from https://sitel.com.mk/anketa-na-ipis-nad-70-od-gragjanite-se-protiv-francuskiot-predlog

Gurakuç Kuçi holds a PhD in International Relations and the History of Diplomacy, obtained from the State University of Tetova in North Macedonia. He completed his master’s studies in International Politics and holds two bachelor’s degrees, one in Political Science and another in Journalism, from the University of Prishtina “Hasan Prishtina”. Currently, Kuçi works as a senior researcher at the Institute for Hybrid Warfare Studies “OCTOPUS”, contributing to analyses and research on the dynamics of conflict and peace in the context of hybrid warfare. He is also a professor at Universum College, where he teaches specialized subjects in his field. With extensive experience cooperation with non-governmental organizations and in journalism, Kuçi has developed a comprehensive portfolio of scholarly publications in international journals, emphasizing the importance of a critical approach to security and global political issues. He is committed to advancing knowledge and scientific research in his areas of expertise.